Backbone Microwave Relay Network

The enigma of Backbone has been with us for over 30 years since Peter Laurie first referred to the use of microwave relay towers in his 1967 Sunday Times article on civil defence. Three years later he expanded the article into the groundbreaking “Beneath The City Streets” in which he says “The GPO planned a chain of concrete towers code-named Backbone which linked the 3 major cities, as well as having connections with the air-defence chain”. Unfortunately, whilst mentioning a role for Backbone in both civil defence and air defence he assumed that the system linked “secret sites”, a belief founded on the mistaken, but perhaps understandable assumption that the civil defence sites the government said it would provide existed but because they could not be seen they must be secret. Unfortunately, we now know they they could not be seen because they did not actually exist. Later editions of the book largely dropped the idea of Backbone as part of a communications network for “secret sites” but continued to maintain, correctly, that it had some military function.

Writing some 10 years later Duncan Campbell gave us some more details in “War Plan UK” saying that Backbone had been conceived in 1954 for a wartime role but with a peacetime one of feeding international communications into the US listening base at Menwith Hill. Both authors mentioned that microwave systems like Backbone would be less vulnerable than cables to sabotage. With this thought in mind it is interesting to note a suggestion made in a book called “Roland Perry - the Fifth Man” which speculates that Baron Rothschild was the fifth man in the Cambridge spy ring. This book suggested that in the early 1960s the Russians funded a string of petrol stations in Britain under the name Nafta which were sited in out of the way places where they could be used as sabotage bases to destroy amongst other things the Backbone stations. This is perhaps not as far fetched as a recent suggestion that the Backbone masts were sited to coincide with “ley lines”.

(Hunters Stones)

There were some early mentions in public documents of Backbone although these were often vague and it is perhaps only with the benefit of hindsight that we recognise their true subject. The first public mention of what we know as Backbone came in the 1955 Defence White Paper which announced “The Post Office…are planning to build up a special network, both by cable and radio designed to maintain long distance communication in the event of an attack”.

An article in the October 1956 edition of the Post Office Electrical Engineer’s Journal (POEEJ) gave a surprising amount of technical detail about Backbone although again without being very specific -

“The first use of microwave systems by the Post Office was for the transmission of television programs; the Sutton Coldfield station of the B.B.C. was initially linked to London by a radio-relay chain in 1949, and the Kirk O’Shotts station has been served by a system from Manchester since 1952. …The first embodiment of a system designed to the new Post Office specifications will be a main radio link between London and Scotland with branches at intermediate points. The main link will carry six broad-band channels in each direction; one or two of the broad-band channels would be for use as a standby. Following hard on the heels of the above “backbone” system will be the development of radio-relay systems for up to 2,000 telephone channels, or about 1,000 telephone channels together with one television channel.”

As we will see later this article describes the system we know as Backbone but no purpose is given for the system but it hints that a functional justification for the microwave system was to provide the additional bandwidth required for television distribution. This argument was given to Duncan Campbell when he made enquiries about the system in the early 1980s. But the General Post Office could equally well have used coaxial cables for television purposes. The first and second London - Birmingham coaxial cables had both been designed with television in mind and parts of the second L-BM cable are still used to carry television programmes. Whilst microwave links have given extra capacity, television alone would not have provided an overwhelming argument for establishing new microwave links.

The POEEJ article gave an artist’s impression of the base stations for the radio links -

We should not get over-excited about the use of the word “backbone” in this early article. As many people have pointed out “backbone” is a common term in communications technology to simply mean a central carrying system, there are references from as early as 1909 to “backbone trunk telephone circuits”. We are however concerned with a specific system which was officially referred to as backbone with a capital “B”.

Further details of the system trickled out. For example a Ministry of Housing & Local Government news release, from 15th March 1957 announced -

“RADIO STATION TO BE BUILT IN CHILTERN VILLAGE: GOVERNMENT DECISION. The Government have agreed to the siting of a Post Office radio station on land to the west of the London-Fishguard road (A.40) … near Stokenchurch, Buckinghamshire. [material omitted] The station is required by the Post Office primarily for the purpose of national defence but it will also have civil uses.”

It seems odd that this and other public reports from planning enquiries openly refer to a facility with an important defence function given that this was at the height of the Cold War and only 6 years before the Spies for Peace caused uproar by revealing the existence of the RSGs. At the time the government said that the existence and siting of the RSGs was not secret but their functions were. But the defence function of the new microwave system was openly made public.

Some of the Backbone sites were the subject of planning enquiries and luckily for us these give us some further hints. For example in January 1961 The Times announced -

“The PO, Ministry of Works and Bucks CC were criticized by the Director-General of the Nature Conservancy at the public enquiry over a proposed radio station site in the Chilterns, which ended at High Wycombe yesterday. [much omitted] Mr J Lawrence, appearing for the Postmaster-General, said the radio station would be essential to Britain’s defence policy. It would be a key point linking a chain of radio stations in a national network of communications which would be vital in time of attack, when normal landline communications might be destroyed.”

So there were a few hints about what the system was for but these did not attract a wide audience. We had to wait until records were released by the National Archives to confirm some of what Laurie and Campbell had suggested and to fill in some gaps.

National Archives files show that the plans for national defence communications in the early years of the Cold War were as grandiose as they were financially impractical and they went beyond Backbone. In 1956 the Official Committee (of civil servants) on Civil Defence suggested that landline communications were vital to -

- The air defence of the UK, particularly to link ROTOR (GCI) sites to the Air Defence Operations Centre

- The nuclear bombing retaliatory effort

- Control of naval operations

- Control of civil and military home defence forces, particularly with the Seat of Government

- The linking up to Central Government and Fighting Services headquarters of long distance overseas communications

The 1956 paper said that these requirements could not be met by the existing cable system for telephones and, more importantly telegraph because the long-distance cable network went through cities and would be disrupted by an attack. It went onto say that Post Office plans to protect wire communications were based firstly on using a number of secondary cables, the “skeleton cable network”, supplemented by backbone radio links and “radio stand by to line links”.

Here we have the 3 elements of the strategic network developed in the 1950s to provide a survivable communications system initially during the expected prolonged war involving atomic weapons and then from the mid-1950s when the strategy changed during and after a very short one involving hydrogen bombs when the post-attack aim would be simply to survive -

The skeleton cable network

This was to consist of a multiplicity of cables up and down the country which did not pass through the largest towns. This was a development of plans from the very early 1950s which aimed to protect communications by constructing -

- Deep level accommodation for a “central unit of trunk service equipment in London” and in 5 “very important industrial towns” with at least one deep level cable tunnel from each to a point outside the target area.

- Strengthened surface buildings in less important towns

- Some dispersed buildings for switchboards in the cities and towns in 1. and 2.

- Ring cables to bypass certain large towns.

The “deep level accommodation” resulted in the underground exchanges in London, Manchester and Birmingham which were all started around 1951(although Kingsway In London was originally planned to be completed in 1949) and completed some 3 years later. Similar exchanges for Liverpool, Glasgow and Leeds were contemplated but along with at least half of the other schemes mentioned below were never started due to lack of money. London was also to have a scheme to protect transmission equipment for central government and the FEDERAL exchange which was to be built alongside the mysterious PIRATE scheme for underground protected accommodation somewhere around or under Whitehall.

London would have a carrier ring main bypassing the capital some 30 - 60 miles from its centre. Other ring mains were considered for Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow, Bristol, Leeds, Liverpool, Derby and Newcastle.

Other towns such as Chester, Nottingham and Swansea would have “zone schemes” which may have been schemes to disperse the central exchanges whilst other places such as Plymouth and Belfast would be included in the protected buildings schemes.

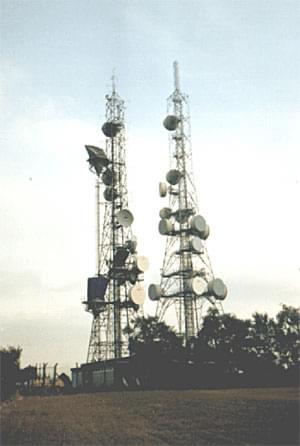

Backbone radio links

The 1956 paper said that the cable network could only provide a skeleton service and would in any case take many years to complete and would therefore need to be supplemented by the Backbone radio link [nb the report did use a capital “B”]. Backbone would consist of 14 radio stations each situated at least 10 miles from a likely target running south to north up the country with spurs to Grantham and Shrewsbury. The station buildings would consist of a tower for the aerials surrounded at the base by a windowless, protected structure to house apparatus and staff and provide protection against blast and fall-out. This confirms the details of the sketch from the POEEJ article but it seems that in practice none of the stations were built with any blast proof accommodation. The perspex shrouds shown in that sketch were also not included in final constructions.

The report also confirms the POEEJ article when it said that the scheme would provide 4 working broadband channels and 2 standbys. Each working channel would have capacity for up to 600 circuits and 2 would be available for defence circuits whilst the other 2 would be used to meet peacetime telephone trunk and TV developments.

The Backbone stations would form a high capacity network literally acting as a backbone for line-based communications. Cables from public, defence and other networks would connect to the stations which acted as terminals or nodes in the network. The messages would then be routed along the network to the appropriate receiving terminal where it would be directed back into the cable network. Originally co-axial cables were used to give the required bandwidth although today fibre optic cables would usually be used. Other stations in the network would act simply as relays passing signals received onto the next station. Some stations are now used by several services and will act as both terminals and relays. Most stations would work automatically and be unmanned.

Radio standby-to-line

Even with Backbone many defence service private wires were still provided entirely by cable. The purpose of the radio standby-to-line scheme was to provide alternative channels of communications to cable, which although they might not go through vulnerable cities still depended on numerous vulnerable repeater stations. It would also be easier to protect a relatively small number of radio relay stations so the idea was developed of a series of radio links from the Backbone stations to military stations. Each link would carry 25 - 150 private wires. The 1956 plan shows radio standby-to-line routes connecting 5 ROTOR Sector Operations Centres (SOCs) into Backbone sites. The Barnton Quarry SOC in Edinburgh is not included but perhaps it would be linked to the northern extremity of Backbone at Kirk o' Shotts. One very interesting link would have gone from West Malling [Fairseat] to Kelvedon Hatch and then to connect to the original southern end of Backbone at Tring, which was later replaced by Stokenchurch. Another route then went west from Tring to Box which would serve the ROTOR SOC as well as Admiralty establishments in Bath, the army switching centre at Boddington [Cheltenham] and various other radio and radar sites in the south west. This route from West Malling to Box may be the origin of the idea of a western Backbone route. Other standby - to - line stations would link the ROTOR sites at Ayr [Gailes], Boulmer and Sneaton Snook to Backbone.

The 1956 report included a map of the proposed system -

Backbone as proposed in 1956

Coalville

Returning to Backbone, a lot of the PRO information comes, perhaps surprisingly, from Countryside Commission records. They show that by 1956 the plan was for a chain of 11 sites running south - north through the centre of England called radio relay stations, radio beam stations or radio stations. The sites would be at Stokenchurch, Charwelton, Coalville( Leics), Pye Green (Cannock, Staffs), Sutton Common (Macclesfield, Cheshire), Saddleworth, Hunters Stones (Harrogate), Azeley Tower (Ripon), Richmond, Muggleswick Common (Stanhope) to Bewcastle Fells (or Cold Fell) near Carlisle.

Three further towers were quickly added at Lockerbie (Dumfries), Lowther Hill (Dumfries) and Kirk o' Shotts (Lanarkshire) to take the chain into Scotland. The sites were to be a maximum of 35 miles apart on a line-of-sight basis.

This initial plan had to be modified for various reasons but by 1959 the sites for the Backbone chain had been more or less finalised. The Tring site was now to be at Stokenchurch several miles to the south although the exact location was not resolved until 1960. This was considered to be the key site where to quote a 1960 report “the North, West, South and East routes come together and where the radio route can be readily extended into London without requiring additional stations and where it can be connected to existing cable routes.”. Charwelton would use an existing GPO site while a new site officially called Coalville (although it is nearer the village of Copt Oak) would be shared at with Leicestershire County Council who were already using it. New sites would be needed at Pye Green and Sutton Common and negotiations to buy them were at an advanced stage. It proved difficult to acquire a site at Saddleworth and an existing site at nearby Windy Hill was adopted.

Corbys Crag 1975

The Hunters Stones site met with considerable opposition from the Society for the Protection of Rural England (SPRE) but they eventually agreed that if a site must be chosen in the general area the GPO’s preferred option was acceptable.

In a letter written in April 1960 the GPO said “We now need this station urgently to meet a civil telephony requirement as well as the defence requirement…Expansion of the trunk telephone network between Manchester and Newcastle will depend on the early provision of the new station and Hunters Stones has to link up with the other existing PO radio stations”.

Assuming this letter, which was not classified, is correct and taking it at face value it is very interesting. Firstly, it suggests that civilian needs were important; secondly it may suggest that the siting of the Hunters Stones station was by this time fixed by the needs to link it to other stations and thirdly it argues against Duncan Campbell’s original suggestion that the Hunters Stones tower was sited to serve the Menwith Hill sigint station. In fact Menwith Hill did not become operational until 1959 and was not taken over by the National Security Agency until 1966.

Certainly, high capacity links were established between Menwith Hill and the Hunters Stones tower by 1975 but it now seems likely that the proximity of the sites is co-incidental rather than planned.

By 1959 the GPO were proposing to replace both the Azerley and Richmond Hill sites with one at Arncliffe Wood. SPRE objected but lost. They also objected to the site at Muggleswick for which negotiations were already under way.

It appears that by 1959 the stations beyond Muggleswick had been reconsidered. Cold Fell was abandoned and replaced by an existing site at Corbys Crag where the local planning authority had gained the false impression that an existing 70 foot TV mast would be replaced by the new 220 foot mast “required for Service Department communications systems…”. Corbys Crag was the last English site to be acquired being finalised by November 1961. Unfortunately, the available records give no information about the northward march of Backbone into Scotland.

There is no suggestion in these records that Backbone was meant to go anywhere other than the south - north route with the east - west extensions across the midlands where Shrewsbury appears to correspond with “War Plan UK’s” Albrighton. There are however hints of what happened after say 1960. One of the oddities about the history of Backbone, and it is tempting to say that this could only happen in Britain is that a project apparently needed for national defence at the height of the Cold War could be delayed by what would now be called the environmental lobby notably the SPRE, the National Trust, the National Parks Commission and, perhaps most surprisingly, the Fine Arts Commission. This was because many of the sites which had to be away from built up areas and on high ground were in what we would now call environmentally sensitive areas. These bodies had to be consulted and the delays this entailed together with those self-imposed by the GPO and the lack of funds from central government seem to argue against the Backbone being particularly important. However, the planning enquiries which these bodies required give us some important insights into the scheme.

Five Ways

This original Backbone scheme plan was conceived in 1954 apparently primarily for defence and plans were actively being made by 1956 but the plan ran into various problems with equipment design and site acquisition. Following the Strath Report there was also a reappraisal of the need for such strategic communications systems.

Now the planners assumed that the next war would be over very quickly and there was no need to provide for “due functioning” so the need for these survivable communications systems diminished.

But more importantly, and as usual for civil defence there was no money to implement the plans and even in 1957 the Official committee on Civil Defence was saying that there was only funds to complete half of Backbone but by then the plans had already been deferred so that it was planned that the southern part of Backbone would not be complete until 1962 and the northern part not until 1964.

It appears that around 1960 many more microwave stations were planned with perhaps the most well known being the towers in the centres of London (started 1961), Birmingham (started 1963) and Manchester. These towers together with ones in Bristol and Leeds are in direct contradiction of the original idea that Backbone would provide a route by-passing the major cities which might be attacked in war and suggest that the new stations had different priorities.

One of these later “post-Backbone” stations at Wotton under Edge attracted a lot of attention. In December 1962 a public enquiry was held into this proposed site which gives us a lot of information about official thinking. The GPO witness to the enquiry said that the GPO was responsible for communications up to and after attack and therefore its services must be provided in advance. Nearly all the long distance circuits were underground and passed through densely populated areas and might be damaged by an attack. Radio stations would be less likely to suffer damage and consequently as a safeguard against attack the PO supplemented cable by a radio-relay network which must 1. avoid population centres and 2. be survivable. He added that the primary need was for defence and the Wotton tower was needed to link to 4 adjacent ones. A map provided did not specify these 4 sites but it is noteable that it has an ‘arrow pointing exactly towards the Five Ways mast at Corsham’. The mast here was built in the early 1960s and probably only carried only one horn. Unusually, if not uniquely the mast was truncated in the late 1980s and it is now only half its original height. Corsham is the base of the RAF’s main switching and signal centre and since the 1960s the home of the Defence Communications Network. It was also the site of the central government emergency war headquarters where by the early 1960s the communications were being installed.

The final report of the government inspector heading the Wotton enquiry summed up the GPO case and gave some more revealing detail. He said “An extensive network of radio links has already been established in the UK for relaying TV signals for the BBC and ITA and this network is being extended to provide essential defence telephonic and telegraphic circuits. It is also to meet growing demands for public trunk telephone circuits and additional TV relaying facilities amounting to several thousand phone circuits and TV channels over the next 5 to 10 years. The station which the PO is to establish would be the key radio relay station in this network serving routes to the west, south west, south and east for extension to London.” This paragraph brings out the idea that the station was needed for civilian telephone and TV use but it is important to note that these civilian needs are not really needed for at least 5 years. The “essential defence” need obviously exists. This idea is confirmed in later paragraphs where the Inspector said “It is the responsibility of the PO to plan the telephone and telegraph network to the best advantage should hostilities break out. With this in mind and in consultation with civil and service departments it agreed to provide an alternative radio-relay system network to the established cable network…this policy is in accordance with the White Paper on Defence of 1955.

Sutton Common 1976

In this connection the station must be suitably positioned to connect with existing stations in the main west-bound route which has been positioned to minimise the probability of interruption during war-time.

The station must also be located where the radio routes can be extended to London by means of a route to the east using existing radio stations…” He later added “…the primary need for a radio station near Wotton-under-Edge is to maintain essential defence telephone and telegraph communications…”.

The enquiry in fact considered 2 sites a few miles apart and it seems to have been important that they were on the right contour (ie height above sea level).The Inspector recommended that permission be granted which in September 1963 it was.

Another PRO file mentions stations at Fairseat and Flimwell being acquired in 1962. These appear on the map in “War Plan UK” as non-Backbone microwave link stations but Fairseat may correspond to the West Malling “radio standby to line” station which appears on the 1956 Backbone map. Public enquiries into the Fairseat and Flimwell sites in 1963 refer to a defence need as did the one into the Butser Hill site near Portsmouth. Here the main requirement was said to be for the GPO “…as part of the countrywide telecommunications pattern for telephone services, TV and defence purposes to which they are committed.” The impression the available, albeit limited information, gives is that the new burst of stations built in the early 1960s was primarily for civilian purposes but it would have a secondary and probably incidental military use. But given the large numbers of these new stations and their cost it seems very unlikely that defence needs were a principal driving force because there was never any money available in the home defence budgets to pay for them. It is tempting to speculate that defence needs were cited at public enquiries on the grounds that this would be treated more sympathetically than commercial needs. By 1965 the GPO microwave network covered some 130 stations centred on the new GPO Tower in London which itself could handle 150000 connections and 40 TV channels - a far cry from the capacity of the original Backbone stations.

One apparent oddity of the stations is that while the majority are steel lattice masts a few are elegant “pencil type mast” structures made of concrete as shown in the original POEEJ article. This has lead to considerable speculation as to the reasons for the different types. The answer however seems to be quite simple. In 1962 the GPO wrote “We have designed a concrete tower for those few stations where technically a lattice tower would not be suitable. Our plans for this chain of stations include only 6 such towers…” Evidence to the Wotton enquiry says that in 1961 the Royal Fine Arts Commission approved a design similar to Wotton (ie a pencil tower) for Sutton Common, Pye Green, Charwelton and Chiltern. The missing sixth tower was Morborne Hill, near Peterborough. Further evidence was provided by the GPO witness who said that the general construction of the Wotton tower would be of reinforced concrete with unwrought timber shutters to the external face to give a pleasing appearance to the finished concrete. He said that a similar design has been found aesthetically acceptable by the Royal Fine Arts Commission and added, significantly, that the concrete and the microwave dishes could be painted to blend in with the countryside. So the clue appears to be in the siting of the concrete towers - they are all in environmentally sensitive areas. The GPO wanted to use steel masts because they had a greater load carrying capacity but the concrete ones are less of an eyesore and more acceptable to the environmental lobby groups. Apart from the 6 rural Backbone stations the only other concrete towers are post-Backbone ones in cities - London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and Bristol, or in the case of Tolsford Hill high on the North Downs near Folkestone. They would all be very visible to many people and this adds to the impression that the difference structures were dictated simply by appearance with aesthetics overruling function.

Stokenchurch - as shown in a 1961 press release after criticism of its visual impact

Stokenchurch - as built (although originally horns were fitted rather than dishes

Although Backbone is frequently mentioned in PRO files on home defence in the late 1950s it is hardly mentioned at all in the 1960s. It seems that the original Backbone stations became absorbed into a much larger microwave network and reports speak of “completion of the system which began with Backbone” and “stations supplementing Backbone”. Files which give details of pre-and post-strike communications from the end of the 1960s do not mention it at all.

Sources:

- Bob Jenner

- BT