Deep Level Shelters in London

HISTORY Courtesy Alan A. Jackson’s ‘Rails through the clay’

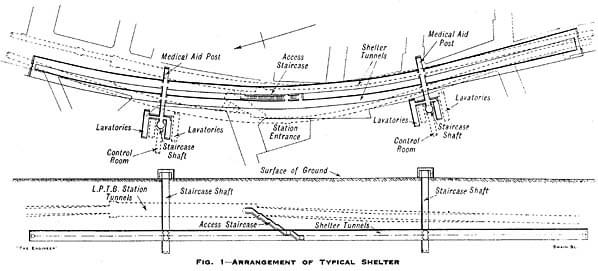

‘The Bombings of 1940 forced a reappraisal of deep-shelter policy and at the end of October the Government decided to construct a system of deep shelters linked to existing tube stations. London Transport was consulted about the sites and required to build the tunnels at the public expense with the understanding that they were to have the option of taking them over for railway use after the war. With the latter point in mind, positions were chosen on routes of possible north-south and east-west express tube railways. It was decided that each shelter would comprise two parallel tubes 16 foot 6 inches internal diameter and 12,000 feet long and would be placed below existing station tunnels at Clapham South, Clapham Common, Clapham North, Stockwell, Oval, Goodge Street, Camden Town, Belsize Park, Chancery Lane and St. Pauls. It may be assumed that at these points the deep-level express tubes would have no stations as the diameter was too small.

Each tube would have two decks, fully equipped with bunks, medical posts, kitchens and sanitation and each installation would accommodate 9,600 people at a construction cost of 15 pounds per head. In the event, the capacity was reduced to 8000 as a result of improved accommodation standards and the actual cost varied between 35 and 42 pounds per head. Work began on November 27th 1940 and it was hoped to have the first shelters ready by the following summer. There were great difficulties in obtaining labour and material and when the blitz abated the Government had second thoughts. The old bogey of ‘deep level mentality’ was brought out of the cupboard by those who opposed the lavish expenditure of money and labour on this project and in the middle of 1941 a select committee on national expenditure recommended that no further deep shelters be built, but those started should be completed. Work at St. Paul’s was abandoned in August 1941 as it was feared the foundations of the cathedral might be affected. Oval was also abandoned shortly after this as large quantities of water were encountered. The first complete shelter was ready in March 1942 and the other seven were finished later in that year. The Board then urged the government to open the shelters to relieve the strain on the tube stations, but the Cabinet were alive to the great cost of maintaining the deep shelters once they were opened and decided to keep them in reserve pending an intensification of the bombing. Towards the end of 1942 part of Goodge Street shelter was made available for General Eisenhower’s headquarters and later two others were adapted for Government use. Another was converted to a hostel for American troops and sections of the remaining four were used to billet British soldiers. These uses were maintained throughout 1943 despite agitation that the shelters should be opened for their proper purpose.

At the beginning of 1944, the air attack warmed up again and on June 13th the V1 assault began to be followed on September 8th by the V2 rockets which then came over intermittently until March 27th 1945. The arrival of the flying bombs finally moved the Government to open the shelters to the public. Stockwell was available from July 9th 1944, Clapham North from July 13th, Camden Town from July 16th, Clapham South from July 19th and Belsize Park from July 23rd. The other three remained in Government use. Regular shelterers at nearby tube stations and homeless people were given admission tickets, but demand was not high and by September some of the spaces available were made available to troops on leave. The highest recorded nightly population was 12,297 bon July 24 1944, about one third of total capacity. On October 21st, two of the shelters were closed again and nightly use fell until by January 1945 only about 25,000 people were using the tube stations and deep shelters. The last air-raid warning of the war was sounded on March 28th 1945 (the European war ended on May 8th), but about 12,000 homeless people and ‘squatter’ continued to sleep in the tubes until May, when the bunks on the platforms were removed and a start was made on tidying up the stations. The 79 shelters stations were closed to shelterers after the night of May 6th and the Board breathed a deep sigh of relief.

After the war, various uses were found for the Government deep shelters, including the storage of documents and the provision of overnight accommodation for students and troops. Goodge Street continued in use as an army transit centre until it was damaged by fire on the night of May 21st 1956. The fire coincided with Parliamentary consideration of a Government Bill seeking power to take over the shelters (The Underground Works [London] Bill) and the Minister of Works assured the Commons they would not again be used for human occupation in peacetime (although no one was killed, the fire had caused some alarm and proved difficult to put out). During the progress of the Bill, it was revealed that the option for railway use had been retained only on the three Clapham shelters and the adjacent one at Stockwell.’

In the 1950’s Chancery Lane was converted into a 500 line trunk telephone exchange with a six weeks food supply and its own artesian well. It was connected to 12 miles of 7 foot diameter deep cable tunnels constructed since the war by the Post Office. Camden Town has been used a as a set for ‘Dr. Who’ and ‘Blakes 7’.

Each set of tunnels had two entrances at the surface consisting of a roughly circular concrete ‘pillbox’ most of them having a square brick ventilation shaft on the roof. This was the ventilation intake fitted with a gas filter. The ventilation exhaust was usually located some yards to one side of the ‘pillbox’ usually consisting of a small brick building or a metal framework around an open shaft. It would appear that the exhaust shaft also served as a loading shaft for heavy or large items as the shaft tops are generally fitted with double doors and a strong metal beam for winching items down the shaft. The ‘pillboxes’ generally had small brick extensions on either side for the entrance doors and some had other small brick extensions attached. Apart from Chancery Lane (and perhaps one entrance at Clapham North) where the entrances were reconstructed during it’s conversion into a protected underground trunk exchange all the ‘pillbox’ entrances remain intact although some of them have been somewhat altered by later use'.

CONSTRUCTION

This rare original document by one of the projects Consulting Engineers; W.T. Halcrow & Partners, gives a fascinating insight into the construction and design of the ‘Deep Tunnel Air Raid Shelters’ (sic).