Brompton Road had a brief and undistinguished life as a station on the London Underground but during WW2 the redundant station was given a new lease of life and played a strategic role in the Capital’s defences against the German Luftwaffe.

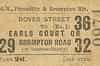

During the early years of the development of London’s underground rail network, the Brompton & Piccadilly Circus Railway was one of the first to receive parliamentary sanction on 6th August 1897, when the company was authorised to build an electrified line between Piccadilly and South Kensington with five intermediate stations at Dover Street, Down Street, Hyde Park Corner, Knightsbridge and Brompton Road. Unfortunately the company was unable to raise sufficient finance and work on the construction never started. In 1899 financial problems forced the delay of another venture proposed by the Great Northern & Strand Railway to build a line from Wood Green to Aldwych.

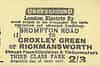

Both lines were eventually revived under the direction of the American capitalist Charles Tyson Yerkes who had played a major role in developing mass-transit systems in Chicago. In 1900, Yerkes decided to become involved in the development of the London Underground network and quickly took control of the Metropolitan District Railway and the unfinished Baker Street & Waterloo Railway where much of the tunnelling had already been constructed. He also purchased the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway and the two ailing schemes, the Great Northern and Strand Railway and the Brompton & Piccadilly Circus Railway which he combined as the Great Northern Piccadilly & Brompton Railway after receiving parliamentary approval for a link between Piccadilly and Holborn.

Two further parliamentary Bills were required to sanction an additional length of line linking Aldwych with the B & PCR’s proposed terminus at Piccadilly. The two companies merged on 8th August 1902 and the Great Northern Piccadilly & Brompton Railway was officially formed on 18th November that year.

CONSTRUCTION

Construction started at Knightsbridge in July 1902 and soon work was underway along the whole length of the route. At Brompton Road, the two station tunnels each 21' 2 ½" in diameter and 350' in length and two 60' 3" deep lift shafts (each accommodating two lifts had been finished by December 1903. Work was still underway on the running tunnels but these and the interconnecting subways between the platforms were completed by 30th June 1904.

By the end of December 1904 the narrower shaft for the emergency spiral staircase had been sunk and the platforms had been largely completed apart from some finishing. By the December 1905, the spiral staircase was in place and the station was ready for tiling which was to include the station name fired onto the tiles in large brown letters three times on each platform. Each station has a different tile pattern to aid passenger recognition, at Brompton Road the tiles were white and cream with green and brown decoration and included embellished ‘Way Out’ and ‘No Exit’ signs.

The street level building stood on the north side of Brompton Road at the junction with Cottage Place; it was designed by Leslie Green to his standard design. The steel framed building was faced with ox-blood red glazed bricks supplied by the Leeds Fireclay Company, with the ground floor divided into wide bays by columns and featuring large semi-circular windows at first floor level. The building was ‘L’ shaped with another face in Cottage Place which was only used by staff. In fact the only door into it opened onto stairs to the upper level. The corner site was occupied by the Gladstone pub forcing the construction of the ‘L’ shaped station building.

THE GNP & BR OPENS…

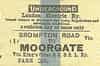

The completed line ran from Finsbury Park to Hammersmith (the section between Finsbury Park and Wood Green was not built at that time). It was ready for use on 3rd December 1906 and after passing a Board of Trade inspection was ceremonially opened by David Lloyd George (MP) on 15th December a year after Yerkes' death. Brompton Road opened with the line although three of the intermediate stations, including Down Street were unfinished and didn’t open until the following spring. A short branch between Holborn and Strand (later renamed Aldwych) opened on 30th November 1907. On 1st July 1910, the GNP&BR and the other Yerkes owned railways were merged by private Act of Parliament to become the ‘London Electric Railway Company’.

From the outset, Brompton Road failed to attract many passengers; it was conveniently sited for the Brompton Oratory and the Victoria & Albert Museum but there was little else to attract passengers as it was very close to both South Kensington to the west and Knightsbridge to the east and from an early date some trains went through Brompton Road without stopping and “passing Brompton Road” was soon to become a familiar call heard by passengers leaving Knightsbridge or South Kensington. One lift was removed in 1911 and the adjacent lift was taken out in the late 1920’s leaving just two lifts in operation and it was clear that the station was being run down in an attempt to save money. The booking office was closed with passengers buying tickets from the lift attendant or machines and in about 1914 the ‘Women’s Institute and club for Underground employees’ was opened in some of the redundant rooms within the entrance building.

…AND CLOSES

The station was closed on 4th May 1926 at the start of the General Strike but when other stations reopened, Brompton Road (and York Road north of Kings Cross) remained closed. The company hoped that the station could remain closed but Brompton Road got a reprieve after local MP William Davidson made an appeal in the House of Commons to the Minister of Transport to have the station re-opened stating that local residents and traders were badly inconvenienced as were those wishing the visit the nearby Brompton Oratory and the parish church. The Minister assured the Honorable Member that the station would be re-opened.

The station did indeed re-open on 4th October 1926 without a Sunday service (hardly convenient for the Brompton Oratory!) but after further intervention from Sir William, the Sunday service was eventually reinstated but the reprieve was to be short lived. Many trains continued to pass through Brompton Road without stopping and by 1929 alternate train weren’t stopping during the week although at weekends most trains called at the station apart from some early afternoon and late night services.

“Since 1909 passengers had become very familiar with trains “passing Brompton Road” and in 1928 the phrase was used as a title for a new West End farce. The show starred Marie Tempest but despite the title the play had little to do with Brompton Road station and revolved around the social ambitions of the central character, Dultitia Sloane, who lived near Brompton Road, and was played by Miss Tempest. Dultitia blamed her lack of society friends on the fact that every other train failed to call at her nearest station, and therefore potential hosts and hostesses overlooked her when it came to delivering party invitations. The production made its debut in Brighton on 11th June 1928, before moving to the Criterion, Piccadilly Circus, where it opened the following month. The reviewers were not exactly ecstatic about it, saying that the storyline was weak, and that it would be best enjoyed “after a good dinner”! Passing Brompton Road' proved reasonably successful however and ran for 174 performances.”

FINAL CLOSURE

The early 1930’s was a time of recession and in order to relieve unemployment Government capital was made available to extend the tube network including the Finsbury Park - Hammersmith line. The scheme included an extension northwards to Cockfosters and westwards to Hounslow and Uxbridge.

As part of the modernisation and expansion programme the closure of uneconomic stations was expected. This also served to reduce running times from the suburbs to the centre of London. York Road and Down Street stations closed in 1932 but surprisingly Brompton Road initially remained open until modernization was completed at nearby Knightsbridge which was provided with new entrances at both ends of the station each equipped with escalators. The improvements at the station left little demand for Brompton Road as the new west entrance at Knightsbridge reduced its catchment area. The station closed after the last train on 29th July 1934 with the new entrance to Knightsbridge opening the following day.

A NEW FUNCTION

At the outbreak of war in 1939, many abandoned tube stations (and those that were still under construction) were adapted as deep level public air raid shelters but the Government had different plans for Brompton Road.

The convenient location of the station with its combination of underground accommodation and a two-storied building above ground made it an attractive location. It was no surprise, therefore, that two government departments showed interest in using it as secure accommodation, but since neither body was aware of the other’s intentions the negotiations soon descended into tragic comedy.

The Office of Works and Public Buildings was interested in storing art treasures from the nearby Victoria and Albert Museum there, whilst the War Office had other designs on the place. Ostensibly His Majesty’s Office of Works had prior claim, having negotiated with the LPTB (The London Passenger Transport Board took over the London Electric Railway Company in 1933) to use the tube station. Independently, the Commander 1st Anti-Aircraft Division, Territorial Army, had held a meeting with the LPTB on 24th May 1938 with a view to locating the Inner Artillery Zone gun operations room (GOR) in the lift shaft of a disused station. Brompton Road was ideal since the building above the station could serve as quarters for the personnel manning the operations room in war conditions.

Two months later, the Board agreed to lease or sell the property to the Army, at the same time confirming a licence to the Victoria & Albert Museum assuming that joint occupancy would not cause problems. This wasn’t to be however and when word reached the Museum in September 1938 that the station might be needed for storing explosives or ammunition, it complained that this would make the station totally unsuitable for safe storage of national art treasures. An immediate refutation from the War Office stated its sole intention was to use the premises as Operations (Control) Room for the guns of the Inner London Defences, 1st Anti-Aircraft Division and a subsequent letter to the Office of Works apologised, but the scheme had to proceed in the interests of national security.

In justification, the OC (Officer Commanding) 1st AA Divisional Signals stated,

“Brompton Road station is ideally situated and a most suitable site for the Gun Operations Room of the Inner Artillery Zone”. He had investigated the question of provision of communications to the station with the telecommunications department of the GPO and ascertained that it would be possible to connect Brompton Road station by cable through the tube to the GPO cables in the underground system. “Safety of lines will thus be assured.” Accordingly the War Office intended to purchase the westbound platform and the lift shafts. “The lift shafts are suitable for the construction of three or more operations rooms and an apparatus room; these rooms can be connected from the spiral staircase. The LPTB is prepared to build the operations and apparatus rooms and to make the ground level bombproof.”

Thus it came to pass that the War Office secured the station for its exclusive use and on 4th November 1938 the Commissioners of Crown Lands purchased the street-level buildings, lift shafts and certain passages for the agreed price of £24,000 (the Museum was awarded the consolation prize of finance to build a bombproof chamber in its own basement). Conversion of the station for its new use then took place. Brick walls were built on the outer edge of the platforms to create rooms inside, while intermediate floors were built in one of the station’s two lift shafts for the operations centre. Of the two walled-off platform tunnels, the eastbound was used as the teleprinter and communications centre, and the westbound one was used for a rest area and staff accommodation.

Throughout the war, the station was the HQ of 1st Anti-aircraft (AA) Division, whose area of responsibility was London and its environs. London Gun Defended area (GDA) was divided into three areas called ‘Inner Artillery Zones’ (IAZ) These were IAZ South, south of the Thames, IAZ North and IAZ East. In addition there was a “Slough and Langley Group” which covered aircraft production in these areas. Normal Administration was devolved through the usual military channels; however the Division was under the operational control of the RAF, in this case the Air Officer Commanding (AOC) No 11 (Fighter) Group, RAF at RAF Uxbridge, who exercised control over all of the South East. This included Fighter Squadrons, Barrage Balloon Squadrons and 1st and 6th AA Divisions.

ANTI AIRCRAFT OPERATIONS

All information received from radar stations, ROC Group HQ’s and other services, that was plotted on the RAF Group operations table was copied to the AA HQ at Brompton Road and displayed on their own plotting tables. Later AA gun sites had their own radar, which enabled them to track enemy aircraft locally.

Guns could not engage until permission had been granted by the RAF Group, Commander. The AA HQ was in direct telephone contact with all gun sites via an open multiphone system.

The plotting room staff were members of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (known as the ATS) which was the women’s branch of the Army. Many ATS worked in AA Command they also manned the control instruments at the gun sites. They did not (officially) ‘man’ the guns.

A vivid impression of day-to-day operations in 1943 is given by retired Lt. Col. B. N. Reckitt in his book Diary of Anti Aircraft Defence 1938-1944. He explains that the original operations room of 1939 was on the ground floor of the street level building. Although later used only as an office, it retained its original plotting maps and was kept in that state for the edification of distinguished foreign visitors to whom it was impolitic to show the real methods of control. The operations rooms actually used for most of the war were at a lower level, built one above the other in one of the station’s former lift shafts. He continues,

“The top room of the lift shaft was called GOR I (Gun Operations Room I), the room of the General Officer Commanding (GOC) who had the picture of the progress of a raid plotted on a large map table below the dais and where he was in touch by telephone with the RAF, ARP and Fire Services, with the searchlights and with every gun site. An elaborate system of coloured lights showed which were actually firing, provided always that the telephonists on the sites remembered to ‘key-in’ the appropriate code. Their forgetfulness was a continual source of trouble with the GOC.

GOR II was mainly a telephone exchange and centre of information for intelligence officers. GOR III, deeper down in the lift shaft, controlled the northern London area and below it GOR IV the southern area and each of these two was in the charge of a Regimental Commander drawn from the respective areas on a rota basis, by night. In each room, the progress of a raid was plotted on maps as in GOR I. The main job of the controller was calling out the gunners for action, plotting the courses of enemy aircraft to them, directing their radar sets to search on the bearings of approaching raiders and ordering ‘barrages’ in the event of saturation attacks. This occurred when there were too many enemy aircraft for radar sets to pick out a single plane for engagement.

GORV was an emergency room at the bottom on the station platform. It never had to be used. In the passage down to it, the controllers and their assistants had to sleep with the lights continually on, in a strong draught and with GPO engineers passing up and down to look after the enormous switchboards, which were also on the old platform. The inn in Brompton Road between the station and the Oratory (The Gladstone) was generally known as GOR VI. When on duty it was the furthest one could go for refreshment.”

GCI RADAR

The Brompton Road operations room took part in an interesting experiment carried out with the Army. A specialised kind of radar, known as ground controlled interception or GCI, situated on the ground scanned the entire dome of the sky overhead to produce a live map of the sky. On this map were plotted all aircraft, hostile or friendly, flying within a radius of many miles. The display tube was known as a plan position indicator (PPI) in which a rotating beam swept the face of the cathode ray tube rather like the second hand of a watch but far more rapidly, producing the display now familiar at air traffic control (ATC) centres. Back then, it was entirely new and one of the first installations was the Army’s anti-aircraft gun installation in Hyde Park during July 1941.

As a further novelty, a remote display and control were provided in the operations room in the tube station, about a mile away. A special linking cable was provided, using BBC equipment, and it was said that the display at Brompton Road was the equal of Hyde Park’s.

Maurice V Wilkes recalled the project in his book, Memoirs of a Computer Pioneer, which notes that,

“The remote display was to be located in the operations room of the 1st A.A. Division, which was underground in a disused tube station in Brompton Road. Someone suggested that it would be worth consulting H. L. Kirke, the chief engineer of the BBC, with regard to the transmission problems involved. 405-line television was operating in London as early as 1936 and was only closed down on the outbreak of war. The BBC had, therefore, much experience of the transmission of video signals. I went to see Kirke in his office and very much enjoyed meeting him.”

Edward Pawley fills in some technical details in his book BBC Engineering 1922-1972, stating that, “among the miscellaneous projects on which the BBC gave advice was the setting-up of a video circuit over a cable pair, using the equipment that had been developed by the BBC before the war, to operate a plan position indicator for gunnery control.”

POST WAR

Brompton Road was meant to be hardened for further use as an anti-aircraft operations room (AAOR) in the early 1950s but was considered unsuitable. Brompton Road’s inadequacy as an AAOR was now acknowledged and a memo from the Director of Military Operations to Vice Chief of the Imperial General Staff (the No 2 position in the army) in November 1951 stressed the urgent need for better protection of military headquarters in war. Six premises, including the headquarters of 1st A.A. Group were noted. In the event, the World War II combination of ground-based observers and radar stations was replaced in the early 1950s by the more sophisticated ROTOR radar stations backed up by new control centres. For this reason post-war use of Brompton Road as an AAOR did not last long, being replaced by three new centres constructed from 1951 onwards and opened in 1953. Boundary changes since the war gave these the following areas of coverage: Lippitts Hill in Essex on the south side of Epping Forest covered the London North GDA (gun-defended area) and Merstham in Surrey controlled the London South anti-aircraft zone with RAF Uxbridge controlling the West London GDA. Brompton Road was retained as a backup AAOR.

With the demise of AA Command in 1956, the three new control centres were themselves redundant when guided missiles replaced gun defence. Other uses were found for Brompton Road and at one time it formed offices for the London District military command. The street level building was later taken over by the Territorial Army. The building was largely intact and unaltered through the 1960’s with some original tiling and signage remaining in the old booking hall. In 1971 there was a proposal to widen Brompton Road. The Gladstone pub on the corner of Cottage Place was demolished that year and in March 1972 the station frontage on Brompton Road was also demolished although the staff entrance on Cottage Place was left untouched and can still be seen today.

An interesting ‘might-have-been’ occurred in 1987, when the site was earmarked for a new £1 million bunker. On 22nd May, the London Daily News reported that the London Fire and Civil Defence Authority had decided to house its control room in the station. The bunker, intended to accommodate 60 civil defence staff, would act as an emergency co-ordination centre for west London following nuclear attack. It was to be one of four bases and was to be ready for occupation within two years. Later, on 19th October, the Daily Telegraph expanded this story, affirming: “The closed Brompton Road Underground station is being converted into a nuclear fallout shelter for local borough councilors to control north-west London in World War III. The station formerly housed the London anti-aircraft control centre; now 60 officials will be self sufficient in a 70' deep bunker for 30 days”." In the event nothing was built.

The station was once again in the news in 1995 when someone attending an Air Squadron function plunged to his death down one of the lift shafts. This wasn’t the first death at the station as on 27th March 1924, a man committed suicide by shooting himself through the head in one of the toilets.

Today the altered street level building and attached drill hall is still owned by the Ministry of Defence and is maintained by the Territorial Army and used as the Town Headquarters (THQ) University of London Air Squadron and the University of London Royal Naval Unit.

Occasional conducted tours of the station have been allowed in the past and in 2000 the children’s television programme Blue Peter was allowed to film at the station including the gun operations rooms but new health and safety regulations have put a stop to all future visits.

WHAT IS LEFT UNDERGROUND?

In theory, Brompton Road could be used for de-training in the event of an emergency evacuation as there is access from the track out through the former staff entrance in Cottage Place but much of the station including the GOR’s lift shafts and spiral staircase remains in MOD hands and even LUL staff are not allowed beyond the top of the stairs leading up from the platforms apart from a monthly inspection of the entire station.

The station is still well ventilated as one of the lift shafts is open to the surface but there is no emergency lighting and subways between the stairs and the ventilation shaft are extremely dirty with everything covered in dust, mainly from train brake linings.

It is possible to get a glimpse of the station from a passing train as the brick walls built alongside the track to create rooms where the platforms once stood are still there. In the centre of the station there is an opening in the brick wall opposite one of the five interconnecting passages between the platforms and a short section of platform remains although it’s unclear if this is original or is a later addition to allow maintenance staff to alight from a passing train. Rail access was maintained after the station was converted but this is described as being at one end of the platform. There are two small rooms entered from this cross passage and one was a switch room where there is still a floor standing cabinet for controlling the air conditioning and filtration plant.

A short flight of steps leads up from the cross passage to a bridge across the eastbound track and on to the lower lift landing used by incoming passengers. The two entrances to the first lift shaft were bricked up when that shaft was converted into the Gun Operations Rooms but the two entrances to the second shaft remain. This shaft is open to the surface and traffic noise can be clearly heard. There is a 7 foot drop down into the lift well and a vertical brick wall has been built across the shaft up to the top so only half of the lift shaft is now used for ventilation. A dismantled fan sits on the lift landing, presumably this was once installed here to aid ventilation.

Back at the cross passage, there are short flights of steps down into the rooms created when the platforms were removed. A number of partition walls survive within these long narrow rooms and much of the original white and cream tiling is still in place although some of it was painted a matt grey during the war and the remaining unpainted tiling is now very grubby. The station name can still be seen in a number of places painted in large brown letters as can the decorated ‘Way Out’ and ‘No Exit’ signs fired into the tiles on either side of many of the cross passages.

At the west end of the west bound platform a projection screen has been painted onto the end wall with a ‘no smoking’ sign below it. This room was used for screening information films for staff. The eastbound platform area was used as the teleprinter and communications centre and the westbound platform area was used as a rest area, this room would also have housed GOR5 in the event of an emergency. The two bridges taking passengers to and from the lifts can clearly be seen crossing the eastbound platform and track.

At the west end of the station, the last cross passage has another stairway up to the other side of the lifts on the lower lift landing, this was originally the way out for passengers leaving the station. At the top of the stairs, there are two wooden doors and once through these the subway turns left across the eastbound track to a locked metal grille. Beyond this grille is MOD property which is out of bounds to LUL staff. Before reaching the lifts, there are two partition walls dividing the subway into three rooms. Once through the second partition the original emergency spiral staircase is to the right and beyond that the GOR lift shaft. One lift entrance has been retained for access into GOR 4 while the original entrance into the second lift has been infilled forming a shallow alcove containing a rack of electrical switchgear.

Before the second (ventilation) lift shaft there is a further partition wall creating a filter room. Outside the room there is a mounted rack of gas filters manufactured by Sutcliffe and Sweetman. A further two racks of gas filters are to be found inside the room together with the controls for the air conditioning plant which is located in the adjacent lift well. There is a flight of steps down into the well where there is a large fan feeding ventilation trunking running through the bunker. The plant is on the opposite side of the brick wall which partitions the shaft, observed from the opposite landing. It turns out the partition in this shaft is actually two walls enclosing a staircase which zig zags across the shaft through four semi circular rooms that have been built within it. The lowest room is entered at the top of the first stairway. There is a brick plinth along one side which might have been some kind of equipment mounting and vertical trunking (intake and exhaust) running up the shaft, but other than that the room is empty. At the far end of the room a doorway leads to the stairs that double back across the shaft up to the next level.

The next two semi-circular rooms are completely empty; the top room has another brick plinth and a door at the far side that leads to a short passage. This leads into the adjacent ‘Gun Operations Room’ lift shaft and into the first of the circular gun operations rooms, GOR1. Apart from ventilation trunking and some electrical fittings the room is empty. There is a trapdoor in the floor close to the side of the shaft with a ladder down to GOR2 below. A doorway leads out to the top of the spiral staircase in an adjacent shaft. We are now in the basement of the street level building. A separate stairway leads up to the booking office where a door prevents any further progress as this is now inside the TA Centre.

The spiral staircase is still in good condition with much of the original white, brown and green tiling still intact. A short distance down there is a doorway into GOR2 with a wooden board with ‘2’ painted on it hanging on a guard rail just outside the room. Again the room is completely stripped apart from electrical fittings and a vertical ladder up through the trapdoor above, a sign on the wall indicates this is the fire escape. A further trap door gives access to another ladder down into GOR3.

Further down the spiral staircase is the entrance to GOR3, because of its position in the shaft in relation to the stairs a short cantilevered walkway has been constructed to give access to this room. Once again the room is empty apart from ventilation trunking and electrical fittings. There is no trap door in the floor down to GOR4 below. GOR4 is at the base of the lift shaft and entered from the lower lift landing. In this room, which controlled the south London guns, there is a large 1" to 1 mile faded Ordnance Survey map on the wall overprinted with a Cassini military grid and overdrawn with the location of ‘Z rocket battery’ sites. There is a glass window into an adjacent room. Unlike the far side of the lift landing which is very dirty there is no easy route for the dust from the tube operations to reach this area which remains relatively clean and dust free.

Pencil marks on a London Transport plan reproduced in London’s Disused Underground Stations indicate that a separate exit from the bunker was constructed to Brompton Square, to the northeast, and a user of the building confirms that a pedestrian tunnel ran from the lift well to a rotting wooden staircase up to ground level. The surface exit appears to be a squat brick with a concrete cap and small door next to an electricity kiosk inside the railings of Brompton Square, facing Brompton Road. No evidence of this exit route was found underground.

Sources:

- London Transport Museum (old pictures from 1907, 1923, 1925 & 1927)

- London’s Secret Tubes by Andrew Emmerson & Tony Beard - Capital Transport Publishing 2004 ISBN-13: 979-1854142831

- Abandoned Stations on London’s Underground by J E Connor - Pub. Connor & Butler 2008 ISBN 978 0 947699 41 4

- Rails through the Clay by Alan A Jackson & Desmond F Croome - Pub. George Allen & Unwin 1962.

- London Railway Record No 13 October 1997 - ‘Recalling Brompton Road’ by JE Connor Pub. Connor & Butler

- Bob Jenner