Written by Nick Catford/Ken Valentine on 19 April 2001.

PADDOCK was built at the start of the 2nd World War on the site of the Post Office Research and Development Station in Dollis Hill. Its purpose was to act as an alternative underground control and command centre for Central Government should a devastating air attack on Whitehall force Government to evacuate central London. PADDOCK would provide protected accommodation for the War Cabinet and the Chief of Staff of the air, naval and land forces, acting as a stand-by to the Cabinet War Room that was, from 1938, located in the adapted basement of the Office of Works building in Storey’s Gate, opposite St. James’s Park.

As early as 1937 plans were drawn up to move Central Government out of London to the North West suburbs and if that became unusable a further withdrawal should be made to protected accommodation in the western counties.

After the Munich crisis, the suburban scheme received further consideration in the autumn of 1938 and despite some misgivings from the Committee of Imperial Defence who favoured a relocation to the western counties, construction of four underground citadels was authorised, one for each of the armed services and an Emergency War Headquarters at Dollis Hill on the site of the Post Office Research Station. The Admiralty Citadel (Oxgate) would be located at Oxgate Lane, Cricklewood beneath the Admiralty Chart Store with the Air Ministry Citadel (Station Z) at Harrow, beneath the Stationery Office annexe and the Army Citadel at Kneller Hall in Twickenham, the home of the Royal Military School of Music; the latter was never built.

The Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill was first established in 1921 with the main building being opened by the Prime Minister J. Ramsay MacDonald in 1933. Dollis Hill was at the forefront of telecommunications research and as such was considered a major enemy target.At the outbreak of war in 1939, the site was camouflaged, this included netting over important buildings. Colossus, the world’s first electronic computer, was built at Dollis Hill by a team led by Tommy Flowers; it was later used at Bletchley Park for code breaking.

On 14th October 1938 the final plans were drawn up for the construction of the bombproof war headquarters deep underground at the Dollis Hill research station. The same team was employed on the plans as had been responsible for the adaptation of the Storeys Gate War Room. CWR2 as it became known would duplicate the facilities of CWR1 (Storeys Gate), the two major rooms being the map room with a usable wall surface of 1000 square feet and a cabinet room with seating for 30 people. All these would be located in a sub-basement 40 feet below ground.

The sub-basement would be protected by a roof of concrete five feet thick (probably in two layers with an intervening layer of gravel as a shock-absorber) while over it would be a first basement considerably larger in area, protected by another reinforced concrete roof

three and a half feet thick with similar protection on the sides. The entrance to this citadel would be concealed within a new three-storey building already planned by the Post Office to meet its own peace-time needs; only one storey was eventually built. The cost of the war HQ was put at nearly £250,000.

As built, the citadel was oblong in shape, running parallel with Brook Road under the north-east corner of the research station grounds. The two basements were longer and wider than the surface building with the first basement extending under the pavement of Brook Road.

Excavation started at the beginning of 1939 without attracting much attention although it involved earth-shifting on a massive scale. Construction work and fitting out were finished by June 1940 in line with the original 1938 plan and CWR2 was ready for use by the War Cabinet.

There was no dormitory accommodation at the research station; instead it was proposed to use 60 up-market flats for the purpose. Neville’s Court is located 200 yards to the south east in Dollis Hill Lane, the war cabinet and senior staff and secretaries would have had rooms there while other personnel from the war headquarters would be billeted in local schools.

It was immediately manned by a skeleton staff to ensure that it was in a state of readiness. Should Whitehall be subjected to a devastating air attack Dollis Hill would be available at short notice. Although most Whitehall personnel were convinced that Dollis Hill would be required, Churchill found the thought of leaving central London unthinkable although he realised it might be necessary. Following the start of the London Blitz on 7th September 1940 he immediately visited Dollis Hill to see the new war headquarters for himself. He also approved the plan to knock together two adjoining flats in Neville’s Court to form a double-flat for himself and his secretaries. One week later the Office of Works requisitioned the whole of Neville’s Court for the Government.

Having seen Dollis Hill for himself, Churchill decided that the War Cabinet should meet there in order to ‘try out’ the facilities to ensure that the bunker was able to fulfill its intended role. He stated, “I think it important that PADDOCK should be broken in”. Prior to this meeting Churchill visited the site on a number of occasions on his way to Chequers for the weekend and he showed his wife Clementine and son Randolph “the flats where we should live” and “the deep underground rooms safe from the biggest bomb”.

It was at this time that the war headquarters was given the code name PADDOCK. It is unclear how this name came about. In the 19th century Tattersalls had established racing stables in the area which became known as the Willesden Paddocks. When the stables were cleared for housing after WW1 one of the roads in the vicinity was named Paddock Road and it has been suggested that the name came from there. The real reason however is possibly more mundane. The Government had a list of pre-selected code names and it is more likely that PADDOCK was the next in line. That name was certainly used by Churchill on 14th September 1940 and CWR2 was always referred to as PADDOCK after that date.

Following Churchill’s visits to Dollis Hill he said:

“We must make sure that the centre of Government functions harmoniously and vigorously. This would not be possible under conditions of almost continuous air raids. A movement to PADDOCK by echelons of the War Cabinet, War Cabinet Secretariat, Chiefs of Staff Committee and Home Forces GHQ must now be planned and may even begin in some minor respects. War Cabinet Ministers should visit their quarters in PADDOCK and be ready to move there at short notice. They should be encouraged to sleep there if they want quiet nights. All measures should be taken to render habitable both the Citadel and Neville’s Court. Secrecy cannot be expected but publicity must be forbidden.

The War Cabinet met at PADDOCK at 11.30 a.m. on 3rd October 1940. The meeting was attended by Churchill, twelve other Ministers and the three Chiefs of Staff. Churchill was not impressed by PADDOCK, in a minute to the Cabinet Secretary on October 22nd he wrote “The accommodation at PADDOCK is quite unsuited to the conditions which have arisen” and he told one of his chief war advisors Sir Edward Bridges, “The War Cabinet cannot live and work there for weeks on end …. PADDOCK should be treated as a last resort”

In his memoirs published in 1949, Churchill was a little vague about the location of PADDOCK and the date of the cabinet meeting stating,

“A citadel for the War Cabinet had already been prepared near Hampstead, with offices and bedrooms and wire and fortified telephone communication. This was called PADDOCK. On September 29th I prescribed a dress rehearsal, so that everybody should know what to do if it got too hot. I think it important that PADDOCK should be broken in. Thursday next therefore the Cabinet will meet there. At the same time other departments should be encouraged to try a preliminary move of a skeleton staff. If possible, lunch should be provided for the Cabinet and those attending it.

We held a Cabinet meeting at PADDOCK far from the light of day, and each Minister was requested to inspect and satisfy himself about his sleeping and working apartments. We celebrated this occasion by a vivacious luncheon, and then returned to Whitehall. This was the only time PADDOCK was ever used by Ministers.”

The last sentence is untrue as there was a second meeting of the War Cabinet on 10th March 1941. This was, in part, another exercise to ensure that the war room was still able to fulfill its function but it was also to impress the Australian premier Robert Menzies who was in the country at the time. Menzies was able to address the cabinet with a 40 minute review of the Australian war effort. On this occasion Churchill did not chair the meeting due to a sudden bronchial cold and the meeting was chaired by Clement Atlee, the Lord Privy Seal.

In October 1940, shortly after the first War Cabinet meeting at Dollis Hill, a descriptive note was written about daily life at PADDOCK. “Government now occupied not only the 19 rooms of the basement and the 18 rooms of the subbasement but also the ground floor with its 22 rooms and lavatories. These rooms were used predominantly for work while other workrooms were available in the main Post Office building. Staff could use the Post Office canteen for meals and had living and sleeping accommodation in Neville’s Court, where about thirty NCOs and men were quartered so as to allow a 24-hour guard over the whole complex to be maintained.”

By the end of 1940 the danger of Whitehall being devastated by enemy bombing had receded and in January 1941 Churchill gave up his double-flat in Neville’s Court. When the Germans turned their attention towards Russia in June 1941 it became clear that PADDOCK may never be required. The armed guards were reduced from forty to half a dozen but five rooms at PADDOCK continued to be earmarked for Churchill and his staff, seven for other War Cabinet Ministers, three for War Office chiefs, seven for Home Forces Advanced GHQ and ten for part of the War Cabinet secretariat and Joint Intelligence Committee.

These arrangements continued with little change for another two years into the summer of 1943 when Churchill, warned about the progress of German plans to bombard London with V-weapons, reviewed the list of all available citadels in London and chose as his own safe place not PADDOCK but the bottom floor of the new purpose-built North Rotunda (code name ANSON) in Great Peter Street, Westminster. In the autumn of 1943 the best of PADDOCK’S furnishings and furniture were removed to the North Rotunda.

PADDOCK had now served its purpose and was redundant. A skeleton staff remained until the end of 1944 when the bunker was finally locked up and abandoned.

During WW2 all military, civil and manufacturing sites that were considered important enough to be guarded by the military were given VP (Vulnerable Points) identity numbers. This was done under the Protected Place Order No. 1 (1939). In 1939 for example, London District Command was responsible for the GPO Research Station at Dollis Hill with a VP number of VP56 and Paddock was VP60, by 1941 these had changed, The Post Office Research Station was VP1635 and Paddock was VP1644. After this prefixes were introduced with letters denoting the controlling authority and in 1942 the Post Office Research Station was E9102 (E = General Post Office) and within this site Paddock was a further VP No. O9002 (O = Miscellaneous) which indicated a guarded site within a guarded site.

After the war the upper basement and above ground building were used by the post office as extra laboratory space and some rooms were used for recreational activities; the staff drama group also used the bunker as a changing room after performances. The research station closed 1974 when the Post Office moved out to Martlesham Heath in Suffolk. The Post Office finally vacated the site in September 1976.

For a few years Cadbury Schweppes occupied the building as offices but in the early 1980’s whole site became the Dollis Hill Industrial Estate. It would appear that the bunker was not used during this period.

In 1981 Paddock was suggested as a replacement for the North London Group War Room at Partingdale Lane, Mill Hill at a cost of £300,000. The plan was rejected by the GLC because of water seepage. At that time there was an inch of standing water in the sub-basement. Part of the site was acquired by Network Housing Association in May 1997. Planning permission was obtained in November 1997 for 99 new homes including 37 new build houses. The main post office building which is locally listed by Brent Council was to be retained and converted into 28 luxury flats. The gates and bunker are also locally listed and as part of the sale Brent Council required Network Housing to make the bunker safe and open it on at least two days a year to the general public.

The contract was awarded to Countryside in partnership and work commenced at site in March 1998 and the first units were handed over in August 1999. The site was completed in May 2000. In line with Brent Council’s requirements Network Housing (now Stadium Housing) spent £15,000 on the bunker including pumping out two feet of water that had settled in the sub-basement when the fabric of the structure was damaged during the construction of the new houses above. Pumps were fitted and lighting installed on both levels and in many of the rooms. Today PADDOCK remains very damp with water ingress on both levels but the pumps ensure that the water doesn’t build up to an unacceptable level in the sub-basement.

The first open day was held on 17th April 2002 in a blaze of publicity with both national and local and foreign press and TV coverage and a Vera Lynn look-alike to open proceedings. PADDOCK is now open on two days a year, one weekday in May primarily for local people, schools etc. and a Saturday in September as part of London Open House weekend.

PADDOCK DESCRIBED

There is little evidence of Paddock on the surface today. The above ground surface building in the north east corner of the research station compound was demolished during the construction of new housing in the late 1990’s. There are however still two entrances to the bunker one consists of a steel door in a brick wall in the front garden between two new houses. This was one of the original emergency exits and opens onto a narrow spiral staircase down to the upper basement. The main entrance is along Brook Road to the north at the end of a line of new housing and adjacent to the entrance to the remaining part of the Dollis Hill Industrial Estate where a number of the research station buildings are still in industrial use. A second emergency exit has been backfilled and leaves no trace.

The main entrance consists of a small brick block house apparently contemporary with the adjacent housing and resembling a small electricity sub-station. Access is down a short flight of concrete steps to a locked steel door. This is in fact a small part of the original surface building now clad in brick so that it blends in with the surrounding buildings. The original entrance was on the west side, away from Brook Road, but this has now been sealed with a new doorway cut through two feet thick reinforced concrete to give access directly onto Brook Road.

Once inside the door there is a small lobby area with an empty water tank to one side and a wide stone stairway down to the upper basement. At the bottom of the stairs there is an airlock consisting of two heavy wooden doors with small glass spy holes for viewing. Both doors have been removed from their frames and are leaning against the wall. Halfway down the stairs water pours through a hole in the wall during wet weather and is probably the main source of flooding during the late 1990’s.

Beyond the airlock, the short entrance passage enters halfway along the main north - south spine corridor of the upper basement. There are is an intriguing sign at this junction pointing up the stairs to ‘Floor 28’. The upper basement is ‘Floor 27 and the sub-basement ‘Floor 26’. This doesn’t of course indicate that there are a further 25 floors below the sub-basement but is part of a unique numbering system used by the Post Office in the 1950’s. All the floors of all the buildings within the Research Station were consecutively numbered. One three storey building might have been Floor 8 - 10 with the former PADDOCK bunker being Floor 26 - 28.

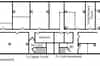

In the upper basement there are 20 rooms on either side of the spine corridor, those on the east side stretching out under the pavement of Brook Road. Some rooms were once further sub-divided but the flimsy partition walls have now collapsed. Most rooms are completely empty and stripped of any original fixtures and fittings and it is impossible to determine what their original purpose would have been.

Turning right from the entrance passage the first room on the right was the kitchen. Although meals were provided in the Research Station canteen above, snacks and light refreshments could be prepared within the bunker and the kitchen would have been further pressed into service in the event of PADDOCK having to be sealed after an air attack. Two Butler sinks remain at one end with a preparation table at the opposite end. There is a serving hatch directly into the spine corridor.

Beyond the kitchen is the main stairway down to the sub-basement. At the top of the stairs is the frame for a substantial steel blast door which has now been removed.

The next room on the right has a wire mesh cage built within it, presumably to provide some sort of electrical screening (like a Faraday Cage). This must be part of a later use by the Post Office and has no connection with the Emergency War Headquarters.

On the right hand side near the northern end is a narrow spiral staircase down to the sub-basement with another narrower blast door frame at the top of the stairs.

Beyond this, in a room to the right there are two pumps mounted on the floor and a bricked up doorway. This was the northern emergency exit spiral staircase which has now been removed and the stairwell backfilled.

At the end of the 120’ long spine corridor is the cable chamber where all the telephone cables would have entered the building. The severed cables can still be seen high on the end wall with cable hangers fixed to the wall with a slot cut in the wall of the adjoining frame room. On the opposite side of the spine corridor is the large GPO Frame Room.

The main distribution frame (telephone exchange) still stands at one end with numerous racks of relays still in place. Each batch of relays has a metal dust cover, some of which are labeled.

One says CWR (Cabinet War Room) and another refers to 100 pairs of cables going to the MDF in the sub-basement and there is indeed a second, much smaller MDF in the sub-basement mounted above a doorway leading into the map room.

This room has obviously been put to later other uses with a lowered ceiling and a large rectangular slot in the end wall to an adjacent room. It is likely that there was once a window here and the two rooms were used as a recording studio and control room at some later date.

Adjacent to the frame roof there is a long room floored with red Darlington tiles.

This was the battery room; it housed two racks of lead acid batteries that would have powered the telephone exchange. There would also have been battery chargers and at one end the pipe work for a sink can still be seen. The sink would have been required if one of the batteries had tipped over with acid leaking onto the floor.

A new doorway has been knocked through from the battery room into the adjacent room. This room was the switch board room, a fact confirmed by one of the few visitors to the bunker who worked there during WW2.

At the far end of the upper spine corridor there is a second narrow spiral staircase down to the sub-basement, again the blast door frame is in place but the door itself has been removed. There are also two plant rooms, one on either side of the main spine corridor. The main plant room is on the east side. This still retains all its plant including fans, compressors, pumps and a floor standing electrical control cabinet with glass doors for the air conditioning plant. From this room metal trunking runs out into the spine corridor where it is suspended from the ceiling, feeding into all the rooms in the upper basement. On the opposite side of the corridor the smaller plant room contains a number of fans and filters enclosed within metal trunking.

After the war, when the pumps were turned off there was always a little standing water on the floor in the sub-basement. In 1982 there was two inches of water on the floor.

The sub-basement is much smaller and only has rooms on the west side of the spine corridor. At the southern end is a third plant room with a large diesel standby generator and its control cabinet, fans, filters and a large battery charger.

Towards the centre of the lower spine corridor several rooms lead into the military hub of he war headquarters, the map room. This room was particularly well lit with a large number of fluorescent light fittings, many of them with angled shades directing the light onto the walls where the maps depicting the war in Europe and elsewhere would have been displayed.

Three of the adjoining rooms have large glass windows overlooking the map room, perhaps one for each of the three services. There is also a message hatch into an adjoining room.

Close to the north end of the sub-basement spine corridor a short side corridor leads to the teleprinter room, this has wooden tables around three sides, power sockets at table height and a small message window into the adjacent cabinet room. The cabinet room is also well lit with angled shades on fluorescent light fittings indicating that this room too had maps on the walls.

The only other identifiable room at the north end of the sub-basement is believed to have been a small studio from where Churchill could broadcast to the nation. There are still some acoustic tiles fixed to the walls.

MEMORIES OF PADDOCK

Paul Sherlock:

“I worked at Dollis Hill from 1962 - 1974. During that time the very impressive main entrance to the Paddock was inside a single storey building known as the Paddock building. The entrance was via a very heavy steel door about 10 inches thick with (probably) 6 large dog catches, like a bank

vault.

The door was flame-cut off, sometime in the early seventies I think. I used a room on the lower floor for a high voltage test lab and for storage for the copper wire used in the coil-winding lab on the ground floor. Also some of the breadboard racks for Tommy Flowers' Colossus computer were still stored there.

The map room was very complete in those days, with the windowed anterooms opposite a large chart wall, presumably with a plotting table in the centre of the room. There were military style portable cots and things around too. People like the motor club used some of the other rooms on the lower floor, where they had a tool hire service. It was rumoured that there was a lower floor, but I do not remember ever finding it. I do remember seeing the generator set though, but it seemed immovably stuck (seized?).

During my time the building and the bunker were clean, dry, and warm. There were sumps at both ends of the main corridor, with float switches keeping the place pumped out. I was quite upset seeing a documentary on the box some years later, I suppose it was when the statute of limitations

expired, as it showed a reporter sloshing through water in his wellies.”

Sources:

- Willesden at War Volume 2 by Ken Valentine. Available from the Grange Museum of Community History.

- After the Battle magazine

Written by Nick Catford on 19 April 2001.

Paddock was built at the start of the 2nd World War below the Post Office Research Station in Dollis Hill. The purpose of the two level citadel was to act as a standby to the Cabinet War Rooms in Whitehall. The bunker became operational in 1940 with the War Cabinet meeting there on 3rd October.

Churchill did not like the new bunker and by the autumn of 1943 the standby cabinet war rooms were relocated to the North Rotunda in Marsham Street, close to Whitehall; Paddock was abandoned the following year.

During the cold war, Paddock was suggested as a replacement for the North London Group War Room at Partingdale Lane, Mill Hill but this was rejected by the GLC. It was also, along with Station Z at Harrow, suggested as the Main Control Centre for the whole of London with the 4 (later 5) Group Controls reporting to it. The idea of 1 central control was never adopted and the upper floor at Paddock was relegated to a Post Office social club.

Following closure of Post Office Research Station, in the mid 1990’s the site was sold to a property developer who converted the Research Station into luxury flats with a new housing estate on the rest of the site. The single storey surface building above Paddock was demolished but the citadel, which has local authority listing was untouched and two access points were retained one an unobtrusive steel door in a wall between two houses and the other a brick blockhouse beside the road which also houses a small electricity sub station. The site has now been handed over to a housing association.

Behind the southern entrance door door is a narrow spiral staircase that descends thirty feet to the upper level of the two level citadel. Signs on the wall indicate this is Floor 27 (the lower level being Floor 28) which seems strange as there were certainly never 26 floors above it. At the bottom of the stairway is some ventilation plant with the air intake trunking and some electrical switchgear.

The spiral staircase enters one end of a 120 foot long spine corridor. Immediately to the left is the ventilation and filtration plant room with everything still intact. Beyond this is a second spiral stairway down to the bottom level. There are rooms left and right along the corridor, most are empty apart from the occasional filing cabinet and table but there is a long room on the far end on the left that still contains a GPO frame. On the right hand side of the corridor in the centre is a wide stone stairway up to a the norther entrance (the original main entrance) and down to the lower level. Beside this is a room with the walls covered in wire mesh which would have given a similar effect to a Faraday Cage although with no ENP during the war it is unclear what this room might have been used for. At the far end of the spine corridor signs point to ‘Emergency Exit’ which would have been another spiral staircase up to the surface. This has been bricked off at the bottom, there is however another spiral staircase down to ‘Floor 28’.

The lower level is (April 2001) flooded to a depth of one foot and in one area a short side corridor and the rooms surrounding it are covered, in sheets of dry rot which is very picturesque appearing a little like cotton wool. There is some evidence of recent new wiring on this level and there are several new pumps lying in the water. This work seems to have been abandoned and the wiring now is probably useless. Again there are rooms on both sides of another long spine corridor. The largest room is the ‘Map Room’ with windows into four adjacent rooms. At the southern end is the main plant room with a standby generator, more ventilation plant and numerous 1940’s control boxes and switchgear.

Those taking part in the visit were Nick Catford, Keith Ward, Tony Page, Robin Ware, Bob Jenner, Andrew Smith, Caroline Ford and Robin Cherry.

During October 2001 the water in the lower level was pumped out and new lighting installed in both corridors, the two flights of stairs, the plant room and the map room. The owners intend to open the bunker to the public (with guided tours) on two days a year.

Written by Ken Valentine on 19 April 2001.

A HISTORY OF PADDOCK

No sooner had the First World War ended than governments started to worry about what might happen in a second one. From 1924 Britain had committees of officials examining ARP questions and this examination intensified after Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933 and as the conviction grew, based on experience in WW1 and in the 1930s, that the bomber would ‘always get through’. It was assumed, naturally enough, that the main target for enemy air raids would be central London.

At the same time there was a strong desire to limit annual defence expenditure, both as a contribution to international disarmament and, in the early 1930s, as a way of minimising the burden carried by a national economy painfully struggling out of depression. By the end of 1935, however, it was clearly no longer safe to assume, as had been assured in the 1920s, that there would be no major war within the next ten years. After the Election of November 1935 it was decided early in 1936 to appoint a Minister for the Coordination of Defence and to launch an expanded five-year programme of rearmament. France ratified a bilateral pact with Soviet Russia and on 7 March Hitler sent his troops into the Rhineland in defiance of the Versailles and Locarno treaties. The Cabinet now called for contingency plans to be devised for coping with a potentially dangerous situation and among new sub-committees set up under the Committee of Imperial Defence was one on “the location and accommodation of staffs of Government Departments on the outbreak of war”.

Chaired by Sir Warren Fisher (Head of the Civil Service), the 5-man sub-committee reported early in 1937 with a suggestion that an alternative centre of government should be planned in the London area where Ministers and possibly Parliament could be relocated if Whitehall were to become unusable. After endorsement by the Cabinet in February 1937, this work was further developed in great secrecy by a new 5-man sub-committee under Sir James Rae (Treasury) and resulted in two alternative schemes, one of which was for accommodating not only civil servants but also Ministers and Parliament in London’s northwest suburbs; if however, this short retreat were to prove insufficient, a further withdrawal should be made to prepared accommodation in the western counties.

For the ‘fighting’ Departments work on bomb-proof underground citadels was to be continued, including one for the Admiralty at Oxgate in north Willesden. In addition, plenty of buildings convertible for use by civilian staffs would be available in wartime London in the form of evacuated schools, especially in a borough like Willesden on the north-west edge of the zone of the capital covered by the Government’s wartime evacuation scheme. At one stage Wlllesden’s schools were scheduled to accommodate some 1,400 civil servants, with Gibbons Road, Leopold Road and Furness Road schools taking about 700 from the external-affairs Departments and Willesden County (Doyle Gardens) and Pound Lane about 500 from the Treasury and the Cabinet Office.

When this suburban scheme was examined further in the autumn of 1938, after the Munich crisis, the Office of Works wished to retain and develop it but the Committee of Imperial Defence preferred to shelve it in favour of the more radical alternative scheme for moving the entire government machine into the western half of the country in one operation. However, construction of four underground citadels would go ahead: one each for the three Services and a fourth which became the bomb-proof Emergency War Headquarters at Dollis Hill.

When war came in September 1939 the Government’s current plan was to shift some 44,000 less-essential officials immediately into the western half of the country but to defer moving some 16,000 of the more-essential officials to various towns in the West Midlands until Whitehall had actually become untenable. In June 1940, however, the situation was changed dramatically by the fall of France, bringing the western half of England within easy reach of German bombers. Moreover, the unhappy experience of the French Government in Tours and Bordeaux suggested that a withdrawal of the British Government from Whitehall to the West Midlands could have a catastrophic impact both on national morale and on international confidence, whereas a regrouping in the north-west suburbs would leave the Government still in London. So the planned move to the West Midlands was now virtually abandoned, leaving the 1938 suburbs scheme as the only prepared alternative.

On 2 September 1940, five days before the start of the London Blitz set off a major invasion alarm, the Chiefs of Staff in a discussion about evacuation schemes noted that the pendulum had now swung away from the radical move to the western counties favoured in 1939 and back towards a slimmer version of the 1938 suburbs scheme: while there would be no general evacuation of Whitehall’s civil servants to the suburbs, a ‘pool’ of suburban schools would be formed with 6,000 places for allocation among any Departments bombed out of Whitehall.

When the Civil Defence volume of the Official History was published in 1955 some of the scheme’s features were still secret and nowhere was the phrase ‘the London suburbs’ clarified further. The following describe in some detail the central place which north Willesden was given in the plans and also what happened in the event, particularly at Oxgate and Dollis Hill. DOLLIS HILL The Research Station In 1914 the first steps were taken towards establishing a research branch of the Post Office’s Engineering Department on the crest of the Dollis Hill ridge; and the first workshops were set up here in 1921. Gradually small permanent buildings began to appear on the eight-acre site and in 1933 the majestic main building, designed and built by H.M. Office of Works was opened by the prime minister J. Ramsay MacDonald.

It was evident that in any future war the pioneering work done on telecommunications at Dollis Hill would be extremely important for the war effort and that the site would be a likely target for enemy bombing. So on the outbreak of war in 1939 the building was concealed beneath a blanket of camouflage netting which made its outlines unidentifiable from the air.

NEVILLE’S COURT Situated in Dollis Hill Lane, opposite the north-east corner of Gladstone Park, is a handsome range of about sixty up-market flats, built c. 1935. Neville’s Court became important in WW2 because it lay, very conveniently, only 200 yards south-east of the research station.

EMERGENCY WAR HEADQUARTERS The path, which led to the creation of a suburban Emergency War Headquarters at Dollis Hill, differed from that which led to the Central War Room complex under Whitehall (Storey’s Gate).

Some time in 1937 the Cabinet called for the planning of an alternative wartime headquarters where Ministers could meet and work in comparative safety. Sir Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence and chairman of the Deputy Chiefs of Staff Committee, handed this task down to his deputy, colonel Hastings Ismay, whose assistant was major Leslie Hollis.

Two possible kinds of location were to be considered: first, a central war room in central London; second a location outside the capital. At an early stage it was pointed out that the phrase ‘central war room’ was a misnomer since what was really intended was an Emergency War Headquarters. But ‘CWR’ continued in use for many years though the initials were officially interpreted from Christmas 1939 as ‘Cabinet War Room’. The main rooms in the complex were to be a War Cabinet room, a Chiefs of Staff room and a comprehensive map room.

By June 1938 it had been decided to construct a Central London CWR in the basement of the Office of Works building in Storey’s Gate facing St James’s Park, which was considered to be the sturdiest structure in Whitehall. The detailed arrangements were entrusted to Ismay and Hollis, liaising with the Office of Works and with the mapping experts of the three Services. Hollis later recorded in his book (1956) that he asked for and obtained the help of the civil servant Lawrence Burgis who had until then been Hankey’s secretary and knew how to handle the civil Departments. But the key man was Eric de Normann, who had joined the Office of Works in 1920 and had recently attended a one-year course of study at the Imperial Defence College; at the time of Munich he was described ministerially as the “linchpin” of the CWR enterprise.

During the summer of 1938 the Storey’s Gate basement was cleared and its ceiling shored up with stout timbers nine inches square, steel supplies being short. Partitions were then inserted to produce a very large map room (where the current situation in all theatres of war could be displayed), a War Cabinet room and a smaller room for the Chiefs of Staff. The whole complex was fitted with air conditioning, an independent power supply and secure telephonic communications with the Service departments, the Foreign Office etc. This protected basement was considered strong enough to survive the collapse of the building above it, especially after steel strutting was inserted in the early autumn of 1938 at the time of the Munich crisis, but the experts knew that it was not proof against a direct hit from a heavy bomb and work on strengthening it was still going on in 1941.

In contrast, the suburban Emergency War Headquarters at Dollis Hill (sometimes called CWR2) emerged from the work of the Fisher and Rae sub-committees, which produced the North-West London Suburbs Scheme. Although not proposed in the Rae Report itself, the Dollis Hill site had evidently been in De Normann’s mind since 1937; and several references to it as the chosen place for CWR2 occur in his correspondence in May 1938. In the same month the Office of Works assigned one of their architects F. M. Dean to “the Dollis Hill job”; but drawings were not examined in detail with Cabinet Office officials until the Munich crisis had given these contingency plans a new urgency.

On 14 October 1938 the three men who had worked together on CWR1 (Hollis, Burgis, De Normann) attended a meeting at the Office of Works in Storey’s Gate at which De Normann presented “preliminary plans” for creating a purpose-built, totally bomb-proof war headquarters deep under the grounds of the Dollis Hill research station. This new HQ would in general replicate the facilities of CWR1, including in particular a large map room with a usable wall surface of over a thousand square feet and a cabinet room with seating for thirty people, all housed in a sub-basement nearly forty feet below ground. The sub-basement would be protected by a roof of concrete five feet thick (probably in two layers with an intervening layer of sand as a shock-absorber) while over it would be a first basement considerably larger in area, protected by another concrete roof three feet thick. The entrance to this citadel would be concealed within a new three-storey building already planned by the Post Office to meet its own peace-time needs. The ground floor of this building would be used for stores for the Post Office engineers' new experimental station. In peacetime the first and second floors would be used by the Post Office for lecture rooms, offices etc. but in wartime they would be adapted for use in quiet periods by a War Cabinet and its secretariat, by the Chiefs of Staff, the Joint Planning Committee, etc; during periods of air attack, however, there would be a general descent into the subterranean citadel. The cost of the war HQ was put at nearly £250,000.

The facts set out above show that the assertion made by Churchill’s biographer Martin Gilbert that the Dollis Hill centre’s “principal focus - the substitute War Rooms - were in an underground section of the GPO’s research centre and had been built as part of the GPO’s own emergency preparations before the war” is quite incorrect. In any case, the GPO did not need a hugely expensive bomb-proof citadel and the Treasury would never have allocated them the money.

Other faulty statements about this citadel have appeared in print since the war. The first mention of it was by Winston Churchill in volume 2 of his book on the Second World War (1949). At this time the official files were still firmly closed and Churchill’s vague statement that a reserve war room called PADDOCK had been prepared “near Hampstead” was knowingly misleading; and the Official History used exactly the same phrase. Churchill also carefully omitted from his book, when quoting his minute of 14 September 1940, the sentence about Neville’s Court in Dollis Hill Lane, which would have been geographically too revealing; but he forgot to delete ‘Neville Court’ when reproducing his minute of 22 October. There was no mention of the Dollis Hill citadel in Hollis’s books or in Ismay’s memoirs but in 1956 a long article appeared in a technical journal about Post Office research work at Dollis Hill (and elsewhere) including a site plan on which the relevant building was clearly marked PADDOCK. Later, in 1971, an edited version of Sir Alexander Cadogan’s war diaries, published a few years after his death, contained a short entry about a War Cabinet meeting held in the “Dolls Hill War Room” on 10 March 1941; this provoked little comment at the time but it induced the writer of Volume Seven of the Victoria County History of Middlesex (1982) to place this war room wrongly in Dollis Hill House at the entrance to Gladstone Park. Some years later, when a feature article in The Times, echoing what Churchill and the Official History had said thirty years earlier, again tried to locate PADDOCK at Hampstead; Nigel West pinpointed its location accurately and clearly in a letter to The Times printed on 28 March 1984.

In fact the citadel, oblong in shape, ran parallel with Brook Road under the north-east corner of the research station grounds. It was both longer and wider than the building erected on the surface and the first basement may have extended under the pavement of Brook Road. Construction work for the citadel started at the beginning of 1939 without attracting much attention although it involved earth-shifting on a massive scale. Some parts of the underground work were not yet complete in January 1940 when the commandant-designate Captain B. F. Adams RN, who was already commandant of CWR1, was taken down to Oxgate by the Admiralty architect to see what his citadel might look like when finished. By the following June, however, the underground citadel had been completed. In conformity with the original plan of 1938 it consisted of a basement roofed over by 3½ feet of reinforced concrete and, at a depth of nearly forty feet below ground, a smaller sub-basement protected by another 6 feet of concrete (probably in two layers); with comparable protection at the sides, the subbasement was considered to be entirely bomb-proof. However, probably through shortage of time, the above-ground building seems to have been limited in the event to the ground floor only, provision for associated office staffs being made in the research station’s main building. By June 1940 Dollis Hill was ready to provide a home for the War Cabinet incomparably safer than the makeshift CWR1 in Storey’s Gate.

During the first ten months of the war, until mid-1940, London could hardly believe its luck. The war had been expected to open with massive air attacks on the capital and in the first three days of September 1939 hundreds of thousands of people, mostly schoolchildren, had been ‘evacuated’ from an inner-London ring, which included Willesden but not Wembley, under a long-prepared official evacuation scheme. But, when London suffered no substantial bombing during the ‘phony’ war, many of these ‘evacuees’ returned to their homes. The collapse of France in June 1940 brought German bombers to the Channel coast, reviving fears of bombing, and a second, much smaller, evacuation from London took place.

By this time, however, the bomb-proof Emergency War Headquarters at Dollis Hill was ready for occupation and De Normann advised Ismay to have the Dollis Hill Citadel all ready and manned by a skeleton staff so that, as soon as there are signs of the position in Whitehall getting too hot, the move can take place at short notice.

At top official level Sir Patrick Duff, permanent secretary at the Office of Works, who had been a member of the Warren Fisher sub-committee way back in 1936, wrote in similar vein to the Cabinet secretary Sir Edward Bridges saying that Dollis Hill was “in a totally different category” from the improvised CWRI, which could never do more than sustain the collapse of the building above it, and that this new “safe place” should now be occupied by a nucleus of selected staff. To drive home the point, Duff offered to take Bridges to look over the Dollis Hill set-up and the visit was arranged for the afternoon of 19 June. Whitehall officials generally were convinced that Dollis Hill would have to be used if Whitehall became uninhabitable; but Churchill himself had a deep-seated aversion to entertaining any thoughts about leaving Whitehall although there was clearly a possibility that a move might have to be made.

With the fall of France Hitler thought that the war in the West was won and that Britain had no alternative to making an agreement with him, which would give him a free hand to tackle Russia. But Britain, led by Churchill, was obdurate, forcing Hitler to the view that an invasion of part of England might be necessary to ensure its future passivity; and the Battle of Britain was fought in the summer of 1940 to achieve local air supremacy over the eastern half of southern England. This carried a danger that at some point London might be heavily bombed in order to draw Fighter Command into decisive aerial combats, but Hitler continued for a time to forbid his pilots to bomb London. It was only after Churchill, with questionable wisdom, sent strong forces of BAF bombers to make repeated raids on Berlin that Hitler decided at the end of August to let loose his bombers on the British capital. A few days later the London Blitz began.

The huge raid on the docks and East End of London, which started at teatime on Saturday 7 September and continued through the night, produced in some quarters a state of alarm bordering on panic. The codeword CROMWELL was issued, warning the defence forces to be ready to meet an invasion, but it was widely misunderstood to mean that the invasion had already started; and some premature demolitions took place. Nor was Whitehall immune. On the Saturday Bridges sent Churchill a paper about the underground citadels and their degree of readiness, which had clearly been drafted some time before but may not have been sent forward earlier because of Churchill’s well-known refusal even to think of leaving Whitehall. It must have made him guiltily aware that he had not done his homework and had never yet visited the Dollis Hill citadel. Historians must ask why Churchill repeatedly sent the RAF to bomb Berlin in the last week of August 1940 without familiarising himself with existing contingency plans for handling the possible consequences of enemy reprisals.

Churchill was still rattled several days later when he called in Duff and accused him, quite unfairly, of having “sold him a pup” by letting him think the Whitehall CWR1 was bomb-proof when it was not. Returning to his office, Duff immediately wrote to Bridges, whom he knew well, to record that he had replied to Churchill’s accusation “with some emphasis”, saying that he had been at pains to assert at every opportunity that CWR1 was not, and could not be made, bomb-proof.

On the morning of 8 September the first thing Churchill did was not to visit the battered East End, as one might infer from his biographer’s account. Instead, he now did what he should have done several weeks earlier: he hurried out to Dollis Hill to see for the first time the emergency war HQ and Neville’s Court. Describing next day the outcome of this “rather unexpected” Sunday morning excursion, Churchill’s office told the Office of Works that he had approved the plan to knock together two adjoining flats in Neville’s Court to form a double-flat for himself and his secretaries. A separate air-raid refuge for his entourage behind the block of flats was considered a good idea. One week later the Office of Works requisitioned the whole of Neville’s Court for the Government.

Churchill also expressed a wish, during or just after his trip to Dollis Hill, to hold a War Cabinet meeting here on Thursday 12 September “so as to give everyone a run over the course” This proposed meeting at Dollis Hill was later deferred until the following Monday and after further slippage eventually took place on 3 October. In the meantime Churchill, who liked to spend his weekends at Chequers, would pause on his way there to drop in first at Dollis Hill and then at Uxbridge (HQ of No. 11 group, Fighter Command). John Colville, his junior secretary, records that on Friday 20 September a two-car party, which included Winston’s wife Clementine and son Randolph, inspected “the flats where we should live” [i.e. Neville’s Court] and “the deep underground rooms safe from the biggest bomb” [i.e. the citadel] where the War Cabinet and its acolytes would work and, if necessary, sleep.

A few days after the Blitz began, the question of code-names was reviewed and the name PADDOCK approved for the Dollis Hill citadel. The reason for the choice is not entirely clear but the name had been well-known in the district for a century, ever since the famous horse-racing firm of Tattersall took over the site of Upper Oxgate Farm where they established a purpose-built stud farm and called its lands Willesden Paddocks. When the Paddocks disappeared under houses after WWI one of the new roads running towards Oxgate from Brook Road, some distance north of the research station, was given the name Paddock Road. The code-name PADDOCK seems to have been used first by Churchill in a minute addressed to Bridges on 14 September 1940; thereafter it was used by officialdom at all times.

Although Churchill never believed that a German invasion was an odds-on possibility, he was emphatic on 14 September about the need to take precautions, having belatedly recognised the need to have alternative accommodation in reserve. Doubtless with an eye on how it would look in a post-war book, he wrote to Bridges: “We must expect that the Whitehall-Westminster area will be the subject of intensive air attack any time now. The German method is to make the disruption of the Central Government a vital prelude to any major assault on the country. They have done this everywhere. They will certainly do it here, where the landscape can be so easily recognised and the river and its high buildings afford a sure guide, both by day and night. We must forestall this disruption of the Central Government.”

What Churchill was talking about here was not the wholesale removal of the Government machine to the western counties (an idea favoured in 1939 but abandoned in June 1940) nor even a general movement into empty buildings in the North West London suburbs (as proposed in 1938) but a strictly limited move of a few hundred key people into the subterranean citadels and associated above-ground accommodation like selected schools. Speaking of the movement of “the high control” from the Whitehall area to PADDOCK and other citadels he said: “We must make sure that the centre of Government functions harmoniously and vigorously. This would not be possible under conditions of almost continuous air raids. A movement to PADDOCK by echelons of the War Cabinet, War Cabinet Secretariat, Chiefs of Staff Committee and Home Forces GHQ must now be planned and may even begin in some minor respects. War Cabinet Ministers should visit their quarters in PADDOCK and be ready to move there at short notice. They should be encouraged to sleep there if they want quiet nights. All measures should be taken to render habitable both the Citadel and Neville’s Court. Secrecy cannot be expected but publicity must be forbidden.”

After dealing in with arrangements for the citadels of the Admiralty, the War Office and the Air Ministry, Churchill concluded:“Pray concert all the necessary measures for moving out not more than two or three hundred principal persons and their immediate assistant. Let me have this by Sunday night, in order that I may put a well-thought-out scheme before the Cabinet on Monday.”

In response to this urgent demand Bridges explained how accommodation at the PADDOCK citadel had been allocated. Besides War Cabinet ministers and their secretaries, an upper echelon of the War Cabinet secretariat, including Bridges and Ismay (head of Churchill’s Defence Office), would move to PADDOCK, leaving the lower echelon under Ismay’s deputy Hollis in Whitehall. The Admiralty and Air Ministry had their own bomb-proof citadels but the War Office would need space at PADDOCK for their Secretary of State, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff with half a dozen assistants, and Advanced GHQ Home Forces. Sleeping accommodation was being prepared in Neville’s Court but temporary billets had been earmarked in the neighbourhood in case the flats were not all ready when needed. Above-ground working accommodation could be made available within 24 or 48 hours in the Post Office research station for Cabinet Office staff who had originally been assigned to Willesden County School, two miles away, but whose presence at the Dollis Hill nerve-centre was later deemed to be desirable.

On Thursday 3 October 1940 PADDOCK finally served the purpose for which it had been created. A meeting of the War Cabinet began at 11.30 am, attended by Churchill, twelve other Ministers and the three Chiefs of Staff, with an agenda of normal range and length. Also held that day in the PADDOCK citadel were meetings of the Chiefs of Staff (including Ismay) and of the Joint Planning Committee, whose secretary was Hollis. Churchill later wrote in his book: “A citadel for the War Cabinet had already been prepared near Hampstead, with offices and bedrooms and wire and fortified telephone communication. This was called PADDOCK. On September 29 I prescribed a dress rehearsal, so that everybody should know what to do if it got too hot. “I think it important that PADDOCK should be broken in. Thursday next therefore the Cabinet will meet there. At the same time other departments should be encouraged to try a preliminary move of a skeleton staff. If possible, lunch should be provided for the Cabinet and those attending it”. We held a Cabinet meeting at PADDOCK far from the light of day, and each Minister was requested to inspect and satisfy himself about his sleeping and working apartments. We celebrated this occasion by a vivacious luncheon, and then returned to Whitehall. This was the only time PADDOCK was ever used by Ministers.”

In fact the last sentence of the this passage is untrue: PADDOCK was used for a later War Cabinet meeting on 10 March 1941. The error is repeated by Churchill’s biographer M.Gilbert in Finest Hour where after saying (p. 800) that “in the event Dollis Hill was never used” he says (p. 823) that “on October 3 the Dollis Hill centre of Government was used for the first and last time Churchill’s error is understandable because he was prevented from attending the 10 March meeting by a sudden bronchial cold and he may have failed to note it in his diary; his biographer has no such excuse as the minutes of the meeting are available.

The second War Cabinet meeting at PADDOCK, like the first, was not held here as a result of a heavy blow dealt to Whitehall during the Blitz. Primarily it was to ensure that the PADDOCK machinery was still in good working order. But there may have been a secondary motive. Although after mid-November London still suffered occasional heavy air raids, the main worry in March 1941 was the thorny question whether British forces, including Commonwealth troops from the Southern Dominions, should be sent from Egypt and North Africa to help Greece to resist a German invasion. The Australian premier Robert Menzies had come over to London on a three-week visit, during which he regularly attended Cabinet meetings, and a meeting at PADDOCK may have been seen as an opportunity to impress him with the depth and thoroughness of British contingency planning. Menzies on this occasion gave the War Cabinet a 40-minute review of the Australian war effort.

In October 1940, shortly after the first War Cabinet meeting at Dollis Hill, a descriptive note was written about daily life at PADDOCK. Government now occupied not only the 19 rooms of the basement and the 18 rooms of the subbasement but also the ground floor with its 22 rooms and lavatories. These rooms were used predominantly for work while other workrooms were available in the main Post Office building. Staff could use the Post Office canteen for meals and had living and sleeping accommodation in Neville’s Court, where about thirty NCOs and men were quartered so as to allow a 24-hour guard over the whole complex to be maintained.

Life was not easy at PADDOCK. One opinion expressed about it in June 1940 was that it would be functioning more like a GHQ in the field than a Government office in Whitehall. On 22 October Churchill told Bridges: “The accommodation at PADDOCK is quite unsuited to the conditions which have arisen. The War Cabinet cannot work and live there for weeks on end, while leaving the greater part of their staffs less well provided for than they are now in Whitehall. Apart from the Citadel of PADDOCK there is no adequate accommodation or shelter and anyone living in Neville’s Court would have to be running to and fro on every Jim Crow warning. PADDOCK should be treated as a last-resort Citadel.”

Three days later the wartime limitations of Neville’s Court were underlined when Sir Patrick Duff described the difficulty of finding a way to construct deep shelters on the site because of the tendency of the ground at Dollis Hill to become waterlogged.

In January 1941 Churchill gave up his double-flat in Neville’s Court (flats 18 and 27) and the armed guard, already reduced from a squad of 40 to one of 20, was about to be reduced further to half a dozen. The danger of Whitehall being devastated by enemy bombing receded when the Germans invaded Russia in June 1941 but five rooms at PADDOCK continued to be earmarked for Churchill and his staff, seven for other War Cabinet Ministers, three for War Office chiefs, seven for Home Forces Advanced GHQ and ten for part of the War Cabinet secretariat and Joint Intelligence Committee, besides the map room, the Joint Planners' room and a room for the Dominions liaison officers. The War Cabinet room was, as at Downing Street, long and narrow, with the prime minister evidently seated half way along one side of a long table.

These arrangements continued with little change for another two years into the summer of 1943 when Churchill, warned about the progress of German plans to bombard London with V-weapons, reviewed the list of all available citadels in London and chose as his own safe place not PADDOCK but the bottom floor of the new purpose-built North Rotunda (to be demolished in 2001) in Great Peter Street Westminster. In the autumn of 1943 the best of PADDOCK’s furnishings and furniture were removed to the North Rotunda, which was known to the War Cabinet secretariat and to De Normann and his colleagues as ANSON - an apt name for a building sheltering a Former Naval Person.

PADDOCK had now served its purpose and was redundant. From December 1943 colonel Ives, who had been for many years in the War Cabinet secretariat and in 1942 had succeeded the naval captain Adams as commandant of PADDOCK, had the job of looking after both PADDOCK and ANSON until the Dollis Hill citadel was finally locked up and abandoned at the end of 1944

The whole of the Post Office site at Dollis Hill was sold off to the private sector before 1980. The citadel is now on Brent Council’s list of ‘locally listed’ buildings.