Down Street is probably one of the best known of London’s closed tube stations for although its life as a railway station was short and uneventful, it played a vital part in the war effort as an underground protected headquarters for the Railway Executive Committee and also provided a temporary occasional home for Churchill’s war cabinet.

During the early years of the development of London’s underground rail network, the Brompton & Piccadilly Circus Railway was one of the first to receive parliamentary sanction on 6th August 1897, when the company was authorised to build an electrified line between Piccadilly and South Kensington with five intermediate stations at Dover Street, Down Street, Hyde Park Corner, Knightsbridge and Brompton Road.

Unfortunately the company was unable to raise sufficient finance and work on the construction never started. In 1899 financial problems forced the delay of another venture proposed by the Great Northern & Strand Railway to build a line from Wood Green to Aldwych.

Both lines were eventually revived under the direction of the American capitalist Charles Tyson Yerkes who had played a major role in developing mass-transit systems in Chicago. In 1900, Yerkes decided to become involved in the development of the London Underground network and quickly took control of the Metropolitan District Railway and the unfinished Baker Street & Waterloo Railway where much of the tunnelling had already been constructed. He also purchased the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway and the two ailing schemes, the Great Northern and Strand as the Great Northern Piccadilly & Brompton Railway after receiving parliamentary approval for a link between Piccadilly and Holborn. Two further parliamentary Bills were required to sanction an additional length of line linking Aldwych with the B & PCR’s proposed terminus at Piccadilly. The two companies merged on 8th August 1902 and the Great Northern Piccadilly & Brompton Railway was officially formed on 18th November that year.

CONSTRUCTION

Construction started at Knightsbridge in July 1902 and soon work was underway along the whole length of the route.

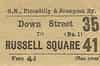

Down Street station was sited between Dover Street (now renamed Green Park) and Hyde Park Corner. The street level building, which was the only entrance, stood on the west side of Down Street a narrow street just off Piccadilly; the façade was designed by Leslie Green to his standard design. The steel framed building was faced with ox-blood red glazed bricks supplied by the Leeds Fireclay Company, with the ground floor divided into wide bays by columns and featuring large semi-circular windows at first floor level. The platforms were at a depth of 60.68 feet and were reached by a pair of Otis electric lifts in a single shaft; there was also an emergency spiral staircase. Down Street was the last but one of the original Yerkes stations to open and the station differs from other Yerkes stations in that is has an alternative emergency exit. From the ‘exit’ subway to the lower lift landing there is a flight of steps which rejoins the standard spiral emergency staircase about one third of the way up the stairs. The parallel platforms were reached by two stairways and were 350 feet long connected by three cross passages.

THE GNP & BR OPENS…

The completed line ran from Finsbury Park to Hammersmith (the section between Finsbury Park and Wood Green was not built at that time). It was ready for use on 3rd December 1906 and after passing a Board of Trade inspection was ceremonially opened by David Lloyd George (MP) on 15th December a year after Yerkes' death. Three of the intermediate stations, including Down Street were unfinished.

Down Street was beset with problems some relating to planning and didn’t open until 15th Match 1907. A short branch between Holborn and Strand (later renamed Aldwych) opened on 30th November 1907. On 1st July 1910, the GNP&BR and the other Yerkes owned railways were merged by private Act of Parliament to become the ‘London Electric Railway Company’.

…AND DOWN STREET CLOSES

Down Street was never able to attract sufficient customers to make it viable. This was partly because of its location out of sight from Piccadilly but also because of the close proximity of Hyde Park Corner and Dover Street. It was sited in a prosperous part of Mayfair where many potential customers already had their own transport. Within two years of opening certain trains didn’t stop at the station and from 5th May 1918 the Sunday service was withdrawn.

When plans were announced to extend the Piccadilly Line to Cockfosters in 1930 a new siding was required between Down Street and Hyde Park Corner for reversing trains and this meant that a short section of the platforms at Down Street would have to be demolished. With no improvement in passenger numbers closure was announced and the last train ran on 21st May 1932 after nearby Dover Street station has been modernised; this included the installation of escalators to replace the lifts. At the same time Dover Street was renamed Green Park with a new entrance closer to Down Street on Piccadilly.

Shortly after closure the lifts at Down Street were removed and a ventilation fan installed at the bottom of one of the shafts. The western headwalls of both platform tunnels were modified and the ends of the platforms removed to allow a step plate junction (a junction where tunnels of differing diameters join - the step is the vertical wall filling the gap between them) to be installed, providing access to a new 836' long siding located between the two running lines at the west end of Down Street; this came into use on 30th May 1933.

A NEW USE FOR DOWN STREET

With the approaching hostilities in Europe a new use was soon found for Down Street. It was inevitable that the railways would become involved in the government’s planning for Air Raid Precautions (ARP) in 1938.

Each of the ‘Big Four’ railway companies made arrangements for functioning under attack conditions and in addition a so-called Railway Executive Committee (REC) was set up by the Ministry of Transport. The panel comprised of senior management from the four main line railways (GWR, LMSR, LNER and SR) and the London Passenger Transport Board. Initially its purpose was to advise the government on how rail transport should be planned and operated in the event of war. On the outbreak of war, however, the railways came under direct government control, with the REC acting as coordinating body between the Ministry of Transport and the individual companies. Protected headquarters for the REC were an absolute necessity and the initial scheme was to strengthen the basement of Fielden House, headquarters of the Railway Companies Association, a body similar to the Association of Train Operating Companies today. Located in Great College Street, Westminster, SW1, the building’s vulnerability to bombing and flooding led to a search for an alternative site deeper underground, such as a disused tube station.

The tale of how Down Street was selected and equipped is told in great detail in two articles by Charles E. Lee in the Railway Gazette (November 17th and 24th 1944). Mr G. Cole-Deacon, secretary of the Railway Executive Committee, was responsible for the design of the offices. The LPTB was put in charge of all structural work, installation of the passenger lift, air raid protection, ventilation and plumbing. Fitting out and electrical, radio and telephone installations were handled by the LMS Railway.

Work was started in April 1939, but by the time war broke out it was only half finished. When on 3rd September the staff of 75 walked down the spiral staircase - a lift was not installed until months later - the rooms had no doors or ceilings. Everything was covered with black dust and in the passages of the tube, with its sloping tiled walls; there was not room for two persons to pass. New works on the station were on similar lines to those at Brompton Road and British Museum and involved walling off the platforms and providing meeting rooms, kitchens, dormitories and other facilities by partitioning the space remaining on the platforms. Further offices, meeting rooms and a typing pool were provided in the low-level subway leading to the platforms from the lift shaft, with gas-proof doors provided at appropriate points.

A few months later the offices were transformed. Mr Cole-Deacon had been a yachtsman and his experience at sea enabled him to utilise every inch of space. The offices were in a short time electrically controlled for ventilation, heating, cooking, lighting, and sewage. Each room had a telephone. Switches were installed that started up a diesel generating plant automatically to light the offices when the main supply was cut off. Perhaps the best way to describe the offices created in the old station (said a report in The Times) was to compare them with the cabins of a modern liner (they were in fact fitted out by the LMS Railway’s carriage works).

CHURCHILL’S WAR CABINET

One section of the offices was called ‘No. 10’ and was built specially for the use of Winston Churchill and the War Cabinet; it was Churchill who gave it its name. It was early one evening in the autumn of 1940 that a senior Cabinet minister entered Mr Cole-Deacon’s room unannounced. He said he would like to see over “this underground hive of industry”, as he called it. He seemed unimpressed until he came to the officers' mess and kitchens and the bedroom quarters. Then he said he had been instructed by the Cabinet to find safe quarters for Mr Churchill, who was absolutely fearless in the raids and if he had his way would prefer to stay at Downing Street. After saying he did not think the offices would be suitable, the minister left, but a short while afterwards telephoned to say that Mr Churchill and several members of the Cabinet would arrive in 20 minutes time.

They came at 7pm when a raid was at its height and an hour or two later a meeting of the War Cabinet was held in the railway conference room. Thereafter, Mr Churchill and his ministers made use of the premises whenever necessary. Mr Churchill was concerned at the interference with the work of the Railway Executive Committee and asked whether it would be possible to construct another suite of offices for the use of the War Cabinet. Mr Cole-Deacon told the prime minister that if he could use an air-shaft for the purpose a complete suite would be ready for use within six weeks. At the end of that period the work was completed and at the same time the heavy bombing of London ended, so that the suite was never used for its intended purpose although both Churchill and his wife used the place as alternative sleeping quarters from March 1941 onwards. During the bombing Mrs Churchill used the platform exit and would travel by tube train to various stations on a surprise visit to platform shelterers.

Churchill referred to Down Street as ‘The Barn’, a name used also in Crossbow committee files. He appreciated, apparently, the ability that working here gave him to continue his work through the air raids - and as a retreat from the distractions of the Cabinet War Room. His access was relinquished in November 1943, however, when it was decided that he should use a different shelter, codenamed ‘ANSON’ if bombing recommenced. ANSON is part of the Rotunda construction.

An amusing story tells how one evening the Prime Minister arrived at his room (which in the daytime was Mr Cole-Deacon’s office) and picked up some papers that the secretary and the chairman of the Railway Executive Committee, Sir Ralph Wedgwood, had been discussing. They were the plans for an intricate railway scheme including the provision of additional lines for shifting traffic from east to west. The plans had not reached the stage for placing before the Cabinet. They were to be considered by the Railway Executive Committee next day, but Mr Churchill, eager to get to work, thought they were for his perusal.

He read through them, grasped what was intended to be done immediately, and made marginal suggestions that were adopted by the members of the Committee at their meeting next morning. The Committee were, however, unaware that the P.M. was the author of the suggestions, as the fact that Mr Churchill and his Cabinet colleagues were using their headquarters as an air-raid shelter was at that time one of the most carefully guarded secrets of the war.

CENTRAL INCIDENT CONTROL

All this discussion about Churchill should not distract attention from the main work of Down Street, controlling the railways. One of the most important tasks during the period of the bombing was that of repairing damage to railway tracks. An incident was reported to the control room at Down Street and whatever the hour of the day or night, the provision of an alternative service was arranged with as little delay as possible to take workers from their homes to the war factories. At this time the maps of the railway systems on the walls of the control room were studded with flags to show where bombs had fallen. The control room was in constant communication with the Admiralty, War Office, Air Ministry, and other Government departments.

At the shortest notice arrangements had to be made for moving men, guns and ammunition, including sea mines, from one part of the country to another. During the D-Day invasion period more than 70 ambulance trains were run each week, and as late as 1946 the control room still had to arrange for more than 2,500 special trains in a period of seven days.

Throughout the war the occupants of these offices 100 ft below ground were entirely safe except for the possible danger from flooding that never in fact happened. To prevent any sabotage and ensure that people who did not ‘need to know’ the actual location of these quarters, an arrangement was made with the Post Office that letters could be addressed simply to R.E.C., London SW (most likely they were delivered to Fielden House, which was in SW and then brought by messenger to Down Street).The GPO telephone line (WHItehall 6146) was also transferred from Fielden House in Westminster to compound the misdirection (it is not known whether similar arrangements were made for other secret installations).

After conversion access was by train, travelling in the driver’s cab and alighting at small platforms in either direction, just as at Brompton Road. Signals were installed to allow personnel leaving the station to halt a train there. Entry was also available via the doorway in the old station entrance at 24 Down Street, although for some visitors this might have created security problems, incurring the risk of recognition. This entrance had a permanent guard of two uniformed police officers.

After the war this hive of activity ended and Down Street remained largely forgotten until the 1990’s although it was retained as a point of emergency egress and new lighting was installed along with signs in one of the cross passages indicating left for eastbound trains and right for westbound trains to help maintenance staff orient themselves on arrival.

In the 1990’s regular tours of Down Street were organised by the London Transport Museum and it soon became a top attraction with a long waiting list for visits. Demand far outstripped the available tours and they were eventually withdrawn when spiraling insurance costs and the difficulty in finding staff to run them meant it was more trouble than it was worth for the Museum.

Part of the 2004 British horror film Creep was set in the Down Street tube station, although the scenes were actually shot at the disused Aldwych tube station and on studio sets. The TV series and novel Neverwhere are mostly set in a medieval-fantasy world with locations named after tube stations such as Blackfriars and Knightsbridge; the finale is located in an area known as Down Street, and one scene of the TV series was filmed on the remaining open section of platform at Down Street, with trains passing by in the background.

In Billy Connolly’s ‘World Tour Of England, Ireland And Scotland’, Billy takes a tour of Down Street station, explaining the heritage and showcasing the various rooms Winston Churchill and his war cabinet once occupied.

SITE VISIT ON 19TH OCTOBER 2001

We walked down a small narrow flight of steps arriving at the top of the original spiral staircase, complete with its maroon and cream tiles so typical of other stations built during the early 1900s.

There were 103 steps in total (23 for the narrow straight staircase and 80 in the spiral shaft, with the shaft itself being 22.2 metres in height). Even at this point, there is evidence of use during WW2. Above is a reinforced concrete and steel cap to prevent bomb penetration down the emergency stair shaft. Behind a door at this level, an emergency generator would have been housed which could provide power for the whole complex below should the mains be cut. The room is now empty, apart from a single tank mounted near the roof. The floor is damp and the room smelt quite musty.

Looking down the centre of the spiral staircase, a space can be seen which had originally been occupied by a small two person lift which was installed to make access easier during the war. The lift itself along with its machinery has long gone but the door still remains along with the remains of the button to call the lift.

We walked down what is a new aluminium spiral staircase that has replaced the old crumbling emergency stairs comparatively recently. Marks on the wall where the old stairs had been flush with the tiled walls could be seen since the new stair way left a small gap between itself and the wall. The new stairs were installed because Down Street is one of the designated as an emergency egress point from the Piccadilly line and for this reason the staircase and corridors down to platform level are reasonably well lit with arrows indicating the way out.

We stopped about two thirds of the way down at a doorway to see a passageway that is unique in an underground station. Through the door is an alternative emergency exit down to the subways below. During WW2, this corridor had been equipped with bathroom and toilet facilities and signs on the wall indicated that this was also an alternative route to the offices below to enable part of the complex to be closed off for privacy.

A wall has been built down the tunnel forming a narrow corridor with doorways to our left opening into several small rooms. The first doorway revealed the toilets, two cubicles containing two porcelain base units, but the water cisterns have long since been removed as has much of the plumbing. The next two doors revealed two bathrooms with baths still in place, one room still has its original electric heater and tank. The final room contains two very dirty wash basins. Going further along this high level subway we turned to the right where there is a flight of stairs down to the subway from the lower lift landing to the platform.

At the bottom of the spiral staircase, the first impression I had of the tunnelling down here was a strange feeling of scale. The passenger subways had been tiled using cream and purple tiling (now very much coated in dust) and are of a larger diameter than similar subways at other stations. It was soon explained that when the station was being built, the railway company was running out of resources and had none of the metal tunnel linings that were usually used to line subways. They did however have an excess of standard rail tunnel sized linings so these were used instead giving an unexpected illusion of scale. The subway we were now standing in would originally have served as the station’s ‘exit’; there is also a parallel ‘entrance’ tunnel from the lifts which we were to see later on.

Along the walls of these subways several painted signs can be clearly seen, one of which reads ‘Enquiries & Committee Room’, a reference to the committee room used during the war. There is also additional evidence of war use here with a slightly raised floor area with a narrow section to our left sectioned off by a hand rail. The raised area was originally walled to provide a separate room which was used as a typing pool for the officers and civil servants that used the complex during its days of active service. We walked around a corner whether there had been a number of other rooms, including a long room for the REC committee and occasionally used as a committee room by Churchill and the war cabinet. All the partition walls in the exit subway were removed in the 1970s to enable ease of access when a new signalling system was being installed in another part of the station and there is now little evidence of their former existence.

To our left was a door to the alternative emergency exit passage. The stairs have a breeze block partition down the middle creating a number of further rooms; the lowest room has a small fan mounted on a concrete plinth. There are two further toilet cubicles at the bottom of the stairs.

After walking a bit further we came to another corner to the right and a short staircase which led down to what originally would have been the platforms. We were now standing at a ‘T’ junction which was one of the five cross passages between the two platforms. The platforms themselves have been removed and the platform area walled off from the running tracks to create a number of further rooms accessed by long narrow corridors.

We were then led onto what originally would have been the eastbound platform; it has been walled off for almost its entire length save the small door sized grilles. Turning left into a small corridor, we then entered a small room which contains electrical switchgear. Strangely, everything in this room is painted grey; even the glass on the dials, the light fitting and the light bulb! This room was used switch between mains electricity supply and the emergency generator.

From the grey room, we were led into a small room which contains the telephone exchange comprising a two-position floor-standing PMBX (private manual branch exchange). This has connections to the public telephone network (WHItehall 6146), private wires and various connections to the railway telephone systems of London Transport and the four main line railway companies; next to it there are a rack of relay sets associated with the switchboard. Next to this is the MDF (main distribution frame) where external lines and internal extension wiring were cross-connected. All this telephone equipment was standard, off-the-shelf and not built especially for Down Street. A thick layer of dust now covers everything.

At the end of this short corridor there is a doorway. This opens directly out onto the tracks and although locked, a quick look through its keyhole clearly revealed another use for the station since its closure; a small portion of the west end of the station has been completely removed to provide access to another tunnel, built soon after the station closed, situated between the main two running tunnels. A siding runs into this tunnel and it is here that failed trains could be temporarily stored or where trains could be reversed.

Along the curved tunnel wall of this room the original station tile pattern can dimly be seen through the grey paint; one of the only places in the station where the original decoration hadn’t been completely obliterated. Here also, someone has carefully removed the paint revealing a perfectly preserved ‘Way Out’ cartouche.

We then continued walking along the old east platform into another bricked off area. This we were told was the old officers' mess, complete with wallpaper and the remains of a button which would have been used to summon the staff! A little further on we came to the kitchen. Although most of the cooking equipment has been (an extraction hood was still there in the 1970s) removed there are marks on the wall where things had obviously been stored and a sink unit can still be seen.

Beyond the kitchen we came to another cross passage with a second stairway up to the parallel subway from the lifts which would have been the incoming subway for passengers. Some old signs can be read through the partially removed brown paint telling passengers which platform to go and directing them to Hammersmith or Finsbury Park.

Before climbing up the stairs we went a little further down the platform area to an interlocking machine room (IMR) built on the platform where some of the war time rooms had been. The IMR houses automatic signalling equipment installed in the 1950s to enable the siding to be controlled remotely. It was not accessible to us so we passed along a further cross passage into a small room on the opposite (westbound) platform, which had been furnished and decorated as an officer’s bedroom during the war.

These small dormitories have been built along the length of the west bound platform. Just above the entrance, a small triangular fragment of the station’s original bull’s eye name board could be seen. This would have taken the form of a red circle with a blue strip bearing the station’s name “DOWN STREET (for Mayfair)”.

Walking along the narrow corridor between the bedrooms we eventually came to a door at the end of the corridor that led out to the small stub of a platform that was left there for access by train during the war. The main access would have been through the street level building in Down Street but if this was blocked following an air raid a train could be hailed by activating a manual signal sited on the platform and personnel would be able to join or alight from the train through the drivers cab.

In this area, sections of the walls still bore the original unique tile pattern for Down Street and in one place the start of the word ‘Down Street’ can be observed, cut off after the ‘w’ by a partition wall.

Back to the second stairway, we then walked up the stairs and along another subway very similar to its parallel neighbour except this one is not used for emergency egress and is unlit.

Turning the corner at the end we came to the ‘in’ side of the lower lift landing. There would have once been two lifts but now the shafts are empty. During the war, three baffles of reinforced concrete were installed in the shaft at regular intervals and a steep stairway built to allow access into the space between the baffles. A metal bridge has been built across the lift well and we walked over this. Beneath the bridge, the remains of an old fan can be seen lying on the floor; this was part of the ventilation system for the complex installed after closure of the station. Down Street was one of the first air conditioned places in Britain, where the air could be purified, warmed or cooled as required. The complex operated on a positive pressure basis, the pressure inside the sealed area was always greater than the outside. That way, any poisonous gases wouldn’t leak into the site. A number of gas tight door were fitted at strategic positions.

Through a small door on the other side of the lift shafts and we were back out again at the foot of the emergency spiral staircase from where we climbed back to the entrance.

Sources:

- London Transport Museum

- London’s Secret Tubes by Andrew Emmerson & Tony Beard - Capital Transport Publishing 2004 ISBN-13: 979-1854142831

- Abandoned Stations on London’s Underground by J E Connor - Pub. Connor & Butler 2008 ISBN 978 0 947699 41 4

- Rails through the Clay by Alan A Jackson & Desmond F Croome - Pub. George Allen & Unwin 1962.

- After The Battle No 12