Although there are a number of admirable web sites devoted to the King William Street station, this one does not duplicate them. So if you want to find out more (and something new!) about this short-lived and long-forgotten tube station jump aboard now…

SIGNIFICANCE

The station’s claim to fame comes from the railway that built it, the City & South London Railway (originally Subway).

This was the world’s first electric tube railway (but not the world’s first tube railway-that honour goes to London’s Tower Subway - nor of course the world’s first underground city railway, London’s Metropolitan Railway, originally run with steam traction). The other significant issue with King William Street station is that it was in use for only a short time, although it found use as an air raid shelter during World War II.

THE CITY AND SOUTH LONDON RAILWAY

The line was inaugurated on 4th November 1890, from King William Street to Stockwell. The Prince of Wales, afterwards King Edward VII, performed the opening ceremony. On 18th December the line was opened to the public. Less than ten years afterwards the line was extended northwards to Moorgate Street and when this was opened on 24th February 1900, new tunnels were brought into service from the Borough, and the original section abandoned. The old city terminus was most awkwardly placed as regards train running, as it faced almost due west and curved sharply to the left under Swan Pier, crossing the river under the up-stream side of London Bridge. There was no intermediate station between King William Street and Borough, which meant that there was no interchange station for London Bridge main line and suburban station. In the case of the down line from King William Street this involved a sharp curve and a gradient of 1 in 30 upon leaving the station, while the up line was still steeper, 1 in 14, through the up line crossing over the down line.

Today the City & South London forms part of the Northern Line of the Underground, with the exception of the bypassed King William Street station and the empty tunnels leading to the abandoned station.

It was assumed passengers would have no interest in looking out at blank tunnel walls on their journey, so only small slit windows were provided. The name of each station was called out when the train stopped. Passengers entered and left these carriages through the ‘lift gates’ operated by ‘gatemen’.

CONSTRUCTION

The line was originally called a ‘subway’, probably to avoid the negative connotations of the smoke-ridden atmosphere of underground lines then worked by steam locomotives. The name was picked up in America, where it caught on and is still in use for what we British rapidly went back to calling an underground railway. The notion of using rope haulage was abandoned some time before the line was actually opened.

KING WILLIAM STREET STATION

The entrance to King William Street Station was incorporated into an existing building at the corner of King William Street and Arthur Street East (now Monument Street) with the company’s offices in the upper floor and the booking hall in the ground floor. The station was 75' below ground and was accessed by two hydraulic lifts within a single shaft; there was also an emergency spiral staircase.

Initially, the station was provided with a single track and two side platforms, one for arrivals and the other for departures. This unusual arrangement prevailed because of the original proposal to use cable haulage required a simple track layout.

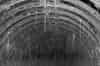

By the time the 10' 2" the diameter tunnels reached King William Street they were side by side and opened into a single 20ft high by 26ft wide bore, which had a 3ft lining of brick, and was finished in white glazed tiling. A signal box was provided at the Stockwell end.

Construction was difficult with regular subsidence due to the water-logged ground around the river but the tunnel and station were eventually completed, with the official opening by the Prince of Wales on 4th November 1890 and the public service commencing on 18th December.

The new line was heavily used from the opening day and the station layout quickly proved unsatisfactory. To overcome this, a Bill was introduced into Parliament in 1882 to construct a new line from Borough to Moorgate Street and abandon the unsuitable terminus. The Bill received Royal Ascent in 1883 but this was for a long term solution. To alleviate the congestion problems in the short term, surface facilities were improved by taking a lease on an existing building in Arthur Street East for a Ladies Room, Parcels Room and Left Luggage Office. A plan to install a third lift was dropped because of cost.

With 15,000 passengers using the station daily, improvements were also urgently required at platform level so the single line was replaced by twin lines running into an island platform which was completed by December 1895. A scissors crossing was added at the south end allowing trains to use either line but this required a shortening of the platform which could now only be used by three car trains.

Work on the extension to Moorgate Street started in 1896 and King William Street closed with the inauguration of the new service from 25th February 1900; the station and the tunnels running under the Thames to Borough were abandoned. Initially no use was found for the tunnels but as early as 1901 it was suggested they could be used for cultivating mushrooms or as a bonded store. The favoured solution was to use the tunnels to carry telephone or electric cables but no user could be found. Initially the track remained in place and was used to store empty stock.

At the outbreak of war in 1914, there were fears that the tunnels might be used by enemy agents and a thorough search was undertaken before the track was removed and the tunnels were sealed up. In 1923 the station was offered for sale or lease.

No 46 King William Street was eventually demolished and in 1933 Regis House was built on the site. The 25' diameter lift shaft was filled at this time but access to the former station was retained using the emergency staircase which was reached from the basement of Regis House. Regis House retained the same quarter-round profile as the older structure. Occasional visits to the old station in the basement were permitted and photographic records of two such there was little change until the outbreak of war in 1939.

PRESS VISIT 1930

In 1930 the Underground took steps to dispose of the old station building at King William Street and shortly after this, the old station and office buildings were demolished to make way for a new block known as Regis House. Before this happened, however, the eminent transport historian and journalist, the late Charles E. Lee, paid a visit to the station in 1930, along with the Daily Mirror. Most likely this press tour was instigated by Lee and then taken up by the Underground. In addition, on 28th March 1930 a number of official photographs were taken and these are still available for purchase from London’s Transport Museum. This is Lee’s description of his visit (Railway Magazine, September 1930, pp 197-199)

“The present means of access is through what was formerly the emergency staircase, and this is reached from a cellar under 46, King William Street, the premises which constituted the booking office of the original terminal station. Descending this gloomy circular stairway by the light of two acetylene flares, our party reached the old platform level with the feeling of having turned back a page of history and recalled those sensations, forgotten by the present generation, which were experienced by the inaugural party through this, the world’s first electric tube railway, some forty years ago. As now existing, the old station still retains sufficient traces of its former equipment to enable a fair idea to be gained of its working condition, although the tracks have been entirely, and the platform partially, removed.

At the platform level the station consists of a circular brick tunnel, with a centre platform and the sites of the lines on either side. Openings give access to the old lift shaft, which formerly contained two hydraulic lifts. The shaft has been covered over and the top portion now is utilised for shop premises. Remains of gas fixtures are a. reminder that the stations were lighted by gas during the first ten years of the railway’s existence, electricity being introduced gradually thereafter. At first only on the newer stations. The ‘King William Street’ station names are still in position in two or three places. At the end of the platform are the remains of the signal box still containing its 22 hand-operated levers. Three of the two-position semaphores are in position. one, at least. of which it may be hoped will be preserved in the company’s museum. Beyond the station, the brick tunnel ceases and the line enters the two iron tubes. Our party proceeded along the left-hand tube. The point where the other tube crosses over is easily noticed. and the two tracks are connected by an iron ladder.

Further on we joined the other tube through a narrow connecting passage on the left and returned to the station. At the mouth of the tubes a much faded board can still be deciphered, notifying “Speed not to exceed 5 miles per hour.” Although all traces of the surface station equipment have long since disappeared, this glimpse into the past may be completed by adding that the original charge of 2d. Ordinary fare for any distance was collected by means of turnstiles; and that this system was maintained until the extension to Moorgate Street made it necessary to introduce fares graduated according to distance.”

A NEW ROLE IN WW II

On the 11th November 1939, it was reported in the Evening Star that work would start to convert the running tunnels but not the station itself into a deep level public air raid shelter. The work, which was expected to last three months, would include the construction of eight entrances, air conditioning plant, seats and first aid posts. This announcement was somewhat premature, but the Minister of Home Security had approved Southwark Council’s proposal in principle. A rent of £100 per year was agreed with the London Passenger Transport Board and work started on conversion of the tunnels into a deep shelter for 8000 people in January 1940.

The first entrance at Marlborough Yard at the rear of 116 Borough High Street was available for use at the beginning of August 1940. The shelter ran between two concrete bulkheads that had been installed in the tunnel at the time of the Munich crisis in 1938, one was just north of the junction with the Moorgate line at Borough and the second was just south of the River Thames which was fitted with a watertight steel door. A similar bulkhead was built on the north side of the Thames. The bulkheads were built to ensure no flooding of the tunnel would take place if the tunnel under the river was breached by a bomb. A strong room was built on the down side of the line just north of the Borough bulkhead to house Council valuables and important documents.

Each new entrance staircase was built using reinforced concrete segments and would allow a flow of 300 people a minute.

Concrete staircases were built inside the tunnels with a void beneath the steps for ventilation, electric cables and water services. A new concrete slab floor was laid in the running tunnels, again leaving a void for services beneath. Some wooden seating was provided on both sides and 12 banks of toilet cubicles were built at intervals along both tunnels. Electric lighting was provided throughout and the walls were whitewashed and at a later date some bunks were fitted.

The shelter came into use on 24th June 1940, six days after the start of the blitz and by August that year thousands of people were sleeping in the tunnel every night even when no air raid warning had been sounded.

King William Street station wasn’t part of this scheme. The Southwark shelter occupied the complete section south of the River Thames and the under river sections were isolated by the concrete bulkheads and watertight doors either side of the river. This left the brick lined King William Street station tunnel and crossover tunnel plus the cast iron running tunnels down as far as the bulkheads beneath Upper Thames Street.

Early in 1940, the owners of Regis House secured a tenancy to use the station tunnel and the crossover tunnel as an air-raid shelter. Various works were required to convert the tunnel to its new use. A mezzanine floor of reinforced concrete was constructed to provide twice the area for use as a shelter. A new floor at track level was also laid. Electric lighting was installed together with two blocks of toilets in the old running tunnels, a kitchen and emergency forced ventilation. An additional 10' 6" diameter shaft, 64 feet in depth, was sunk in Arthur Street with direct access from the basement of King William Street House (on the opposite side of King William Street from Regis House). This connected with the south side of the former crossover tunnel, a short distance from the point at which the two separate running tunnels started. The whole works then formed a private shelter for the office employees of Regis House and King William Street House with the two basement access points. The capacity was stated to be 2,000 persons.

The tenancy was continued after the war so that the tunnels could be used for storage. When visited in the 1970’s the station was still being used for document storage by Regis House.

Writing about the King William Street shelter transport and communications enthusiast Alan Gildersleve states:

“I slept many times in the former King William Street station under Regis House, where my father worked. I was there the night the bomb fell on the Bank station and the tunnel really rocked. The King William Street station was used as offices by the United Dominions Trust and I was intrigued by the PAX extension number 00. Obviously the last remaining spare line circuit in a 100 line PAX! The two running tunnels at the end were toilets apparently running all the way to Borough. One male and one female. The air conditioner made such a noise that when it switched off at about 5 a.m. the sudden silence woke you up! That part that I slept in was north of the Thames, and the only access of which I have any knowledge was from the basement of Regis House (corner of Monument Street) via the standard spiral tube station staircase. This comes out into a double track sized tube tunnel which was much larger in diameter than a normal tube station and then a large office and full of desks and filing cabinets, between which we used to put up camp beds.

It was obviously right next to the running tunnel as we were aroused each morning by the trains starting to run apparently just the other side of the wall! I visualised the new tunnel as running parallel with the old one but apparently, from your map, this was not so. As I said, the two normal sized tunnels ran on from the end of this large one and they were closed off with doors, one marked ‘Ladies’ and the other marked ‘Gents’. Presumably they continued on to join up with the under-river bit. It’s a good job that no bomb fell in the river bed! I used to spend the evening with my father in a store room in the basement, listening to some one else’s gramophone up the passage playing The Breeze and I, If I should fall in love again and particularly A little dash of Dublin. I now have copies of these records (on 78) and they really bring back memories. About 10 p.m. we would make a cup of tea, eat a sandwich and go down to the tube station for the night along with several other employees most of whom belonged to the United Dominions Trust. My Father worked for Watts Watts and Co., who ran merchant shipping and whose ships were mostly named after London districts such as Twickenham, Dagenham and even Dulwich. He was a scrutineer keeping an eye on the invoices which were being received and to see that the firm wasn’t being swindled!”

SUBSEQUENT EVENTS

A press visit was arranged in 1992 for Railway World magazine (April 1992 issue, pp 44-45), in which the late Handel Kardas says inter alia:

“The station was adapted as [an] air raid shelter in the war years, losing its character in the process. The large single-arch lost its platforms and trackbed and the space was filled with two stories of rooms. These are still there, falling into decay, but the original structure seems as good as ever.

Unfortunately they make the old station practically impossible to photograph. Access to the station for maintenance and inspection purposes by London Underground Ltd engineers, is through the office block. In a fashion reminiscent of the opening sequence of The Man From Uncle or similar lightweight 1V spy series, staff enter the building at ground floor level and descend two floors. From there they take a short staircase further down still, to an innocuous-looking locked door. This gives access to another world of old, musty tunnels and twisting stairways, which show that this pioneer station was remarkably like many later ones in general design. Much of it was originally tiled and the L T Museum has had several sections of tiles professionally salvaged for preservation. Soon, redevelopment will start and this remarkable survival of the first ever tube line will be lost forever.”

A letter from M.E. Mawson of Edenbridge in the following issue took a more positive line, stating:

“I do not understand how the old King William Street terminus may disappear with the forthcoming redevelopment, because it is not underneath Regis House but crosswise to King William Street and ending below the side street towards the monument. The spiral steps are beneath the pavement therein, while the lift was indeed in the building confines and filled in solid when the present block went up. Surely London Underground Ltd will retain access via the basement of any succeeding premises.”

Regis House was demolished at the beginning of 1995 and subsequently replaced by a new building of the same name; access was still retained at the new Regis House. A blue plaque on the side of the building in Monument Street commemorating King William Street. There is no public access to King William Street from Regis House and visits to the station and air raid shelter which have been possible in the past are no longer allowed as the tunnels now carry live cables.

TOUR OF KING WILLIAM STREET STATION & SHELTER

From the basement of Regis House we passed through a door onto the top of the old emergency stairs which descend 75feet to the station below. The stairs appear to be original and in good condition considering their age. The spiral ends 30 feet above the platform from where a concrete stairway runs down to platform level, this still retains its original cream and patterned tiling scheme employed on the early CSLR stations.

The two level shelter constructed in 1940 remain largely unaltered, running along the east side within the station tunnel. Steps at either end of the block of rooms lead to the upper level where some ventilation plant can still be seen. Metal trunking is suspended from the ceiling in both the upper and lower rooms. Previous visitors have noted a number of WW2 propaganda posters still in good condition but these have all now largely disintegrated following recent changes to the ventilation of the station area. It is still possible to make out a couple of the poster fragments including one that once said “Careless talk costs lives”. One typed sheet is still in place which says “Special notice to late arrivals and early risers: please spare a thought for your fellow shelterers and refrain from making any unnecessary noise. Please remember others may be asleep although you are not”.

At the east end of the station there is a side room, perhaps a toilet, that still has tiled walls and a tiled ceiling. A walkway runs along the south side of the station where some wall tiling is also still in place. At the end of the ‘building’, on the site of the crossover at the end of the platform, there is a kitchen with a serving hatch close to a small fan which feeds into the ventilation trunking. There is also the bottom of a circular brick shaft with a bricked up entrance. This was the 64' shaft sunk from King William Street House in 1940.

The two tunnel mouths are slightly offset in level. There are two rows of whitewashed brick toilet cubicles in each tunnel mouth, one tunnel for men and the other for women; a narrow walkway runs between the two lines of cubicles. Immediately beyond the station the tunnels turn sharply to the left below Swan Street before terminating at a concrete bulkhead close to the Thames; at this point both tunnels are flooded to a depth of 1 foot. There is a metal door through the bulkhead but we had no permission to go beyond this.

The original running tunnels north of Borough tube station remain, although when the Jubilee Line Extension was built in the late 1990s the old southbound tunnel was cut through as part of the construction works at London Bridge station in order to provide the lift shaft situated at the south end of the northern line platforms. These running tunnels now serve as a ventilation shaft for the station and the openings for several adits to the old running tunnels can be seen in the roofs of the Northern Line platform tunnels and in the central concourse between them. The remaining sections of twin tunnels between London Bridge and Borough are still intact. A number of posters can still be seen as can steps up to the various shelter entrances.

A construction shaft between London Bridge and King William Street, beneath Old Swan Wharf, now serves as a pump shaft for the disused sections of running tunnels. It is no longer possible to walk through between the two stations as the old C&SLR running tunnels have been blocked off with concrete bulkheads either side of the River Thames. This work has cut the through ventilation and the tunnels and especially the spiral stairs are now very humid. In recent years new lighting has been installed at King William Street and the station and west running tunnel now carry new cabling for the underground network

Sources:

- London Transport Museum

- London’s Secret Tubes by Andrew Emmerson & Tony Beard - Capital Transport Publishing 2004 ISBN-13: 979-1854142831

- Abandoned Stations on London’s Underground by J E Connor - Pub. Connor & Butler 2008 ISBN 978 0 947699 41 4

- Rails through the Clay by Alan A Jackson & Desmond F Croome - Pub. George Allen & Unwin 1962.

- The City & South London Railway by TS Lascelles - Oakwood Press 1987 ISBN 0 85361 360 5

- The Railway to King William Street by Peter Bancroft - Published by the author 1981 ISBN 0 9507416 0 4.

- Railway Magazine September 1930 - The Worlds First Electric Tube by Charles E. Lee.